Thanatology for Oncology Pharmacists

Robert Mancini, PharmD, BCOP, FHOPA

BMT Pharmacy Program Coordinator & PGY2 Oncology Pharmacy Residency Director

St. Luke’s Cancer Institute, Adjunct Clinical Instructor – Oncology

Idaho State University College of Pharmacy

Boise, ID

No, this is not an overview of the most recent Avengers movies, but rather a discussion on a concept we all face every day as oncology practitioners, death and dying. While my first thought when learning the term was the Titan Thanos, the concept is not far off. The term thanatology is derived from the Greek mythology “Thanatos,” which is the personification of death. Thanatology as a professional discipline came into the public limelight in the 1960s and 70s after two key publications, The Meaning of Death by Herman Fiefel in 1959 and On Death and Dying by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross in 1969.1-2 In the latter, Kubler-Ross outlined the now-famous five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

We as pharmacists, especially those practicing in oncology, deal with death and dying on a frequent basis. The most recent statistics from the American Cancer Society state that the 5-year overall survival rate for all cancer combined is approximately 67%, indicating a mortality rate of 33%. Said another way, one in three patients will die from their cancer.3 This may differ depending on the type and stage of cancer, and is unmatched in other areas of practice outside hospice.3 Despite this, pharmacist education/ training on topics surrounding death are woefully inadequate.

Surveys suggest 68% of pharmacy schools include some form of death education in their curriculum, compared to 95-96% of nursing and medical schools. Most of us would likely state we are not prepared to have conversations with patients about the topic.4 In fact, in a study evaluating pharmacist perspectives after implementation of physician-assisted suicide, 93% of respondents said their pharmacy degree did not prepare them for said interactions.5 While some schools have started to focus more education with guided electives, there is a lot more we can do to help pharmacists in their education related to death and dying.4,6

In looking back at my journey with this topic, in my teaching at Idaho State University (ISU) College of Pharmacy, I can reach as far back as my first year of Pharmacy School. In my Law and Ethics course during my P1 year, I was asked to read Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom. That was the first impact that made me realize there was more to being a pharmacist than the therapeutics. During my fourth year APPEs, by which time I had already realized I wanted to specialize in oncology, I was able to spend one of my rotations at an inpatient hospice facility working with an interdisciplinary team whose whole focus was care of the dying patient.

Then, during my PGY2 in oncology, there was a conversation that caught me off guard. Though it was more than a decade ago, I still remember it. I was dispensing lenalidomide to a gentleman in his 80’s who asked me: “If this were you, would you do it?” How does one answer that question when it isn’t me; when my life has not been as long or full as his? So many thoughts ran through my mind, most notably, why was I never prepared to have this conversation?

Fast forward a few years, I am now the Residency Program Director (RPD) for our PGY2 program and I am finding more and more oncology pharmacy residents struggling with the same questions. This led me to two points, first to develop an elective for pharmacy students to think and talk more openly about this topic, but second to ensure that I incorporated talks related to this during hospice and palliative care rotations for my PGY2 residents. Since then, I have found a huge benefit for students, residents, and myself to continue to review and focus on this topic.

Now, the question becomes, how can you integrate such topics in your own practice, either for yourself or for your students, residents, employees, or coworkers? Former students, residents and colleagues have introduced me to many of these resources over the years, and those introductions have proven invaluable.

For me personally, one of the books that helped me most in my approach to patient care was Mitch Albom’s The Time Keeper.7 It centers around the concept of the time we have on this earth with two competing paradigms, a young girl who is ready to give up on life and an old man who wants to live forever. It really helped me realize that there is no one patient specific factor that can predict how a person will react to the decision to pursue treatment for cancer. By looking beyond what we see and understanding the patient’s goals and priorities, I was able to learn how to better discuss such difficult conversations, even when I may not have agreed with them personally.

While the articles and guidelines tell us what we should do in someone with Stage IV breast cancer, for example, they can never address the personal decision making that goes into those choices. This has helped me better accept the choices our patients make, including the reality of death and acceptance of that inevitable endpoint. I believe this has been a key component in avoiding emotional burnout in my practice.

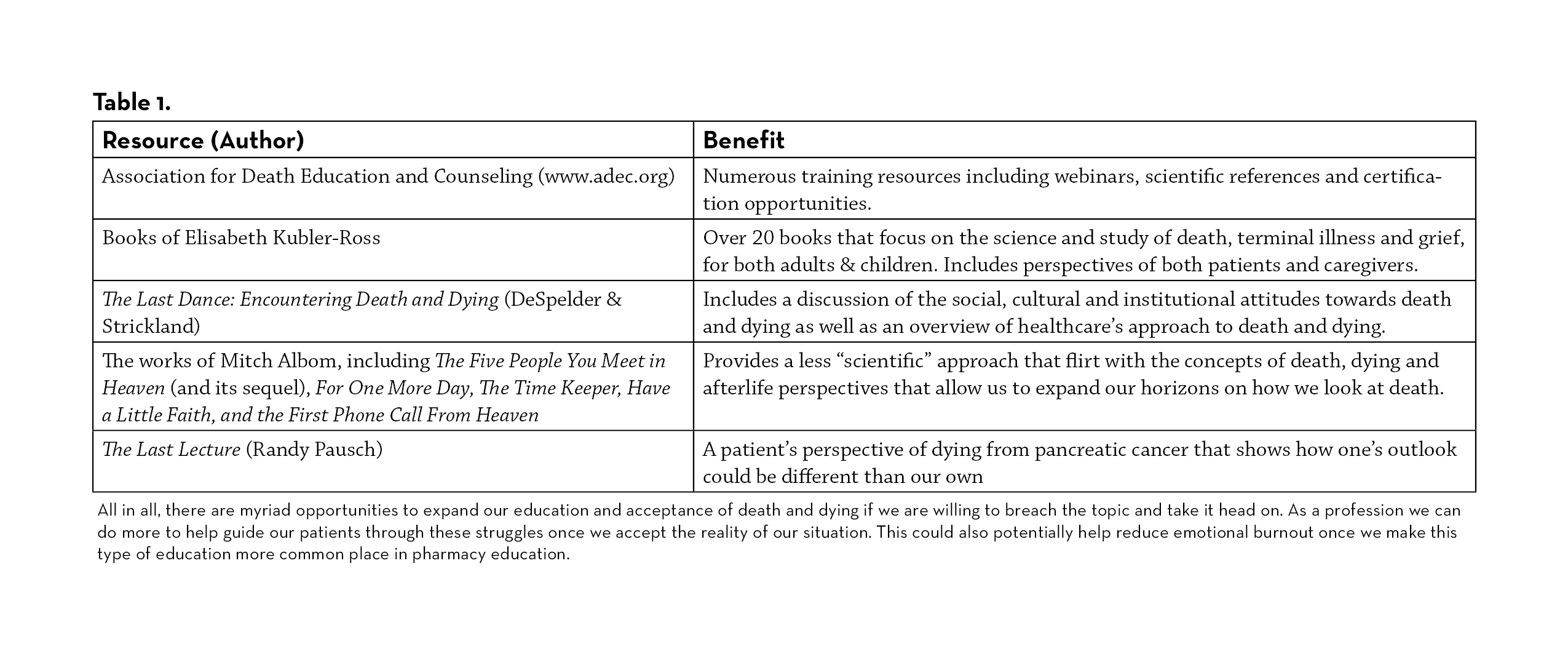

There are a multitude of resources depending on how in depth you want to go. Reading many of these books and reviewing these resources (see table 1) have helped me in many ways over the years including finding the need to bring more of this education to our pharmacy students and residents. For those in academia, it is important to find ways to incorporate this topic into your classes or electives, wherever possible. A survey of students at ISU who took my elective course found that their self-assessment in “awareness of the complex psychosocial issues that oncology patients face,” increased by over 5 points (on a scale of 1-10). There are many ways I have incorporated this theme into my teaching opportunities including both scientific and theoretical resources. I actually require my elective students to choose one of those books to read for the course and write a paper putting themselves in the shoes of a terminal cancer patient to understand why someone may or may not pursue treatment.

All in all, there are myriad opportunities to expand our education and acceptance of death and dying if we are willing to breach the topic and take it head on. As a profession we can do more to help guide our patients through these struggles once we accept the reality of our situation. This could also potentially help reduce emotional burnout once we make this type of education more common place in pharmacy education.

REFERENCES

- Fiefel, H (Ed.). (1959). The meaning of death. McGraw-Hill.

- Kubler-Ross, E. (1970). On death and dying. Collier Books/Macmillan Publishing Co.

- Siegel RL, et al. Cancer Statistics 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7-33.

- Beall JW, Broeseker AE. Pharmacy Students’ Attitudes Toward Death and End-of-Life Care. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(6): 104

- Parr RB, et al. The Pharmacist and patient death: Are we prepared for the emotional and professional impacts? Res Social Adm Pharm. 2019;15: e20

- Manolakis ML, et al. A Module on Death and Dying to Develop Empathy in Student Pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;75(4): Article 71

- Albom, M (2012). The Time Keeper. New York: Hachette Books