HOPA Publications Committee

Lisa Cordes, PharmD, BCOP, BCACP, Editor

Renee McAlister, PharmD BCOP, Associate Editor

Christan Thomas, PharmD, BCOP, Past Editor

Karen Abboud, PharmD, BCPS

Benjamin Andrick, PharmD, BCOP

Lydia Benitez, PharmD, BCOP

Alexandra Della Pia, PharmD, MBA, BCOP

Karen M. Fancher, PharmD, BCOP

Erin Kelley, PharmD

Chung-Shien Lee, PharmD, BCOP, BCPS

Robert Steven Mancini, PharmD, BCOP, FHOPA

Bernard L. Marini, PharmD, BCOP

Danielle Murphy, PharmD, BCOP, BCPS

Alan L. Myers, PharmD, PhD

Gregory T. Sneed, PharmD, BCOP

Kristin Held Wheatley, PharmD, BCOP

Spencer Yingling, PharmD, BCOP

HOPA News Staff

Lisa Davis, PharmD, FCCP, BCPS, BCOP, Board Liaison

Michelle Sieg, Communications Director

Joan Dadian, Marketing Manager

View PDF of HOPA News, Vol. 19, no. 4

Board Update: Time to Celebrate and Look Ahead

Heidi D. Finnes, PharmD, BCOP, FHOPA

HOPA President (2022–2023)

Senior Manager, Pharmacy Cancer Research

Director, Pharmacy Shared Resources, Mayo Clinic Cancer Center

Assistant Professor of Pharmacy, Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine

Rochester, MN

It’s hard to believe I’m writing an end-of-the-year letter already! It feels like I blinked and we went from being in Washington DC in September to the last month of the year. A brief recap of recent HOPA initiatives follows.

“The Practice of Perseverance,” our fall Practice Management Program, was held in Washington DC on September 22. There were more than 130 attendees. Sessions included “Navigating the Balance Between Being a Caregiver and Oncology Pharmacist,” “A Guide to Preventing Medical Necessity Denials,” and “Results, Realizations, and Recommendations from the 2021 Oncology Pharmacy Workforce Survey”.

HOPA had our largest in-person Hill Day to date on September 20, also in Washington DC. Twenty-two HOPA participants, including three from our Patient Advisory Panel, held 43 meetings with elected officials from 16 states. We met with the staff of a number of House and Senate cosponsors of the Cancer Drug Parity Act and secured an additional cosponsor from the House of Representatives. Along with the Oncology Nursing Society, who were also on the Hill that day, we picked up substantial support for the bill to Improve Access to Cancer Care.

Hill Day and other Advocacy efforts were highlighted during October’s Town Hall. On October 18, we gathered via Zoom with our Advocacy and Public Policy team. I was pleased to hear so many members ask how to get more involved during the live Q&A! To learn more about our grassroots advocacy, please go to hoparx.org/advocacy and click Get Involved. There, you can learn to set up meetings with policy makers, start using use our Legislative Action Center, and more.

HOPA’s Wellness Task Force is committed to supporting HOPA members. They have created a Wellness and Burnout Statement to acknowledge the critical need and commitment from HOPA to mitigate risk factors of burnout and support well-being initiatives. Please read the statement on our website. It is currently featured in the homepage banner at hoparx.org. You’re your calendars for the next Quarterly Town Hall with HOPA’s Wellness Task Force on Tuesday, January 17 at 2 pm CST.

The HOPA-ASCO 6-Month Quality Training Program is nearing its half-way point as 10 teams of HOPA members gain hands-on experience designing and implementing quality projects. The training culminates with an overview of the projects during Annual Conference 2023, which brings me to my next point . . .

Our Annual Conference will be held in Phoenix March 29-April 1, 2023. The Annual Conference Committee has chosen “Reconnect. Rebuild. Reimagine.” as a theme that reframes the aftermath of COVID-19, burnout, and loss as opportunities for growth and empowerment. I look forward to reconnecting with all of you in Phoenix. Watch for registration to open soon!

Even with everything we have accomplished recently, there is still a lot to look forward to. Early next year, we will roll out the 2023-2026 Strategic Plan, which builds upon our mission and vision. The plan will challenge us all to dig deeper to ensure the hematology/oncology profession remains healthy and patients have access to the best care possible.

Thank you for all you do. See you in the New Year!

Feature: Overcoming Challenges to Provide BiTE and CAR T Cell Therapy at a Community Cancer Center

Krista L. Voytilla, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Oncology Research Pharmacist

St. Luke’s Cancer Institute, Boise, ID

Chase N. Ayres, PharmD, BCOP

Blood and Marrow Transplant/Malignant Hematology Clinical

Pharmacist

St. Luke’s Cancer Institute, Boise, ID

Introduction

Cancer care in the United States is typically delivered within two locations: at an academic or university-based cancer center or at a community cancer center. About 80% of the patients treated for cancer in the United States receive their care in community cancer centers.1 As cancer care evolves with immune stimulating therapies such as chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) and bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs), a robust team of health care professionals is required to assess and manage unique adverse events, particularly cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). Not only are these adverse events a potential concern, but complex methods for medication administration can challenge a smaller community health system. Herein we will review the technical and clinical issues facing community cancer centers and their pharmacy teams delivering these high-tech treatments.

About St. Luke’s Cancer Institute

Located in Boise, Idaho, St. Luke’s Cancer Institute (SLCI; formerly Mountain States Tumor Institute) is a member of the St. Luke’s Health System which serves southern Idaho, northern Nevada and eastern Oregon. We have five full-service cancer centers located within 3 hours of each other within Idaho. Annually our cancer institute sees 20,000 patients with about 5,000 newly diagnosed patients. Oncology pharmacy services provided across centers include pediatric oncology, oral chemotherapy, infusional chemotherapy, autologous and allogenic blood and marrow transplant, CAR T cell therapy and investigational drug services.

BiTE Therapy Planning at a Community Cancer Center

The first FDA approved BiTE therapy, blinatumomab, was approved with accelerated approval for relapsed B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) in December of 2014, with full approval following in 20172. St. Luke’s Cancer Institute participated with the Children’s Oncology Group protocol AALL1331 evaluating blinatumomab administration for first relapse of childhood B-Lymphoblastic Leukemia (B-ALL). The protocol strongly recommended hospitalization for the first 9 days of blinatumomab administration to evaluate for CRS. The remainder of the 28-day cycle could be infused through a programmable CADD® pump for at home administration. Sounds like a simple transition, right?

Outpatient administration of a continuous infusion monoclonal antibody is potentially not an issue when you have a dedicated home care infusion service line at your health care system. But what if these services do not exist? Our first pediatric blinatumomab patient spent both 28-day cycles admitted on the pediatric oncology unit due to lack of dedicated resources to adequately support this patient in the outpatient setting. That is 56 days away from their home, family, friends, and pets.

As the efficacy of blinatumomab was confirmed in the first relapse space, pediatric clinical trials began investigating blinatumomab administration at first diagnosis of B-cell ALL for higher risk patients with detectable minimal residual disease (MRD) and are now looking at high throughput sequencing in patients with MRD negative disease. To maintain quality of life for our patients and their families, and ensure we were responding to change in care standards, our efforts needed to focus on how to support in-home administration of blinatumomab. The focus needed to include not only our pediatric patients, but our adult patients as well, both those participating in clinical trials and those obtaining blinatumomab through commercial avenues as blinatumomab became incorporated into the standard of care.

Takes a Village

A definitive team approach is essential to care for these BiTE eligible patients. Communication and effective processes between pharmacy, nursing, oncology providers, emergency room providers, triage, and patients and/or their families need to be established. Administration challenges with blinatumomab need to be addressed, including prolonged continuous infusion, dedicated intravenous line or access, nursing care for central venous access changes, and technical requirements such as the specific intravenous bags, tubing and need for programmable ambulatory pumps.3 Management challenges with in-home administration also need to be addressed, including processes for continued evaluation for serious adverse events, how to handle interruptions with continuous administration (including a pump malfunction or a pump alerting to warn of an occlusion), and what to do if tubing has been severed or the Port-A-Cath has been accidentally disconnected or de-accessed.

The oncology pharmacy team needs to create a compounding strategy to address the need for this complicated technical compound for both clinical trial and commercially treated patients as well as both pediatric and adult patients, as these two service lines are typically distinct from one another. Discharges from inpatient to outpatient administration also take coordination with home health care services if these are involved.

Education of pharmacy and nursing staff is also important, particularly with staffing turnover, protocol requirements for documentation of pharmacy training, nursing familiarity with adverse events, continuous infusion administration, intravenous line care, and familiarity with battery operated programmable pumps.

Needs and Limitations of CAR T Cell Therapy

Unfortunately, as with many cutting-edge treatment modalities, patient access to CAR T cell therapy is limited by geography and cost. Patients residing in rural areas may be hours away from the tertiary care centers that offer this treatment, often requiring out-of-state travel. Due to the high risk of life-threatening toxicities within the early days of therapy, patients must stay within two hours of the facility for the first four weeks after treatment.4,5 For patients without family or friends with whom to reside during this period, lodging must be prepared. Travel and board are logistical barriers patients must tack on to the already mammoth task of undergoing costly and intensive medical care. Additionally, outside referral and travel incur delays in treatment for patients who are already facing several weeks before therapy may be administered, in the setting of relapsed or refractory disease that may not respond to bridging chemotherapy. Patients have died during this referral waiting period at our institution.

These obstacles may be ameliorated in part by smaller health systems nearer these patients offering CAR T cell therapy. This presents many challenges on the part of the healthcare system, however. Treatment with CAR T cell therapy is a labor-intensive process and requires substantial multidisciplinary input. Additionally, the financial cost of administering CAR T cell therapy cells is higher than comparable therapies such as blood and marrow transplant (BMT).6 The steps to become an authorized treatment center for CAR T cell therapy vary between manufacturers, but all require various proofs of clinical competence and sufficient resources to offer treatment, in addition to the need to have Risk Evaluation Mitigation Strategy (REMS) enrollment in place. This means a center must have an established history of clinical excellence in treating hematologic malignancies. Due to the resource demands of having a BMT program in place accredited by the Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapy (FACT), many programs, including our own, begin CAR T cell therapy delivery within the BMT service line, although some centers may choose to offer this through a separate service line.7-9

Within the CAR T cell therapy service line alone, this includes a team of physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, and pharmacists with training and experience caring for hematology and stem cell transplant patients. Additional education and training of all involved clinical and laboratory staff is essential to managing these patients as well as their subsequent toxicities. Logistically, a treatment center must also be equipped with coordinators and administrative leadership capable of establishing and maintaining the policies, procedures, and other operational standards to meet requirements set by FACT and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).5,10 A treatment center must also have access to apheresis methods to obtain patient T cells prior to shipping off to processing facilities for CAR generation. Outside of the department providing cellular therapy, providers from related specialty areas must be integrated to provide consultation or intensive care during the eventual management of toxicities after CAR T cell therapy administration, particularly CRS and ICANS. Once a center has decided which CAR T cell therapy products to offer and has satisfied the requirements to establish contracts with the associated manufacturing entities, it must also have a network in place to identify and evaluate patients for eligibility.

Overcoming Barriers

Fortunately, St. Luke’s Health System has long served its surrounding community and has a well-established reputation for oncology treatment through St. Luke’s Cancer Institute. Multiple SLCI clinics are present throughout the state and form a crucial referral network within the system, in addition to community sources of referral from outside SLCI. St. Luke’s has offered autologous BMT services for decades and allogeneic BMT since 2018. This has laid a foundation of clinical staff experienced in the complexities of care for this general patient population. In the context of the wide-ranging medical services available within the St. Luke’s Boise Medical Center, the CAR T cell therapy team is able to take advantage of a well-resourced infrastructure to meet the needs of care delivery to these patients. For patients residing farther from the medical center, a Guest House on campus is able to provide lodging within walking distance to both the hospital and cellular therapy clinic for close outpatient follow-up and easy access in cases of emergency.

Having a stable foundation from both a clinical and financial perspective is imperative given the high cost of entry inherent to CAR T cell therapy. Current reimbursement models are inadequate for the initial administration and toxicity management period of CAR T cell therapy patients, so a health system must be able to take the hit upfront to recuperate these losses later in care.11

Looking Forward

BiTEs are here to stay and are an important part of our armamentarium of hematologic malignancies and studies are underway evaluating their potential utility in solid tumors as well. Luckily, many new BiTE therapies in development do not require continuous infusion techniques as the issue of short half-life has been overcome, allowing once weekly dosing.

Delivery of complex, high-cost treatment such as CAR T cell therapy is often left to tertiary care referral centers inaccessible to many patients. However, any community cancer center with an established BMT program may be well-poised to take the next steps toward offering this potentially life-saving treatment to its patients, without the sometimes-insurmountable hurdle of referral to an out-of-state medical center.

As of this writing, our medical center has recently performed its third CAR T cell therapy infusion, with several more patients slated for treatment in the near future. Each patient receiving CAR T cell therapy cells at our facility represents a patient (and family) that has been able to receive cutting-edge standard-of-care therapy, close enough to home to substantially reduce out-of-pocket travel and lodging costs. Likewise, referral within our health system or local community has allowed for shorter time to treatment in patients whose survival often hinges on receiving this treatment before they can be overcome by disease.

As reimbursement models are further delineated and our processes are further refined with experience, our CAR T cell therapy program is expected to grow to meet all the cellular therapy needs of our community. Eventually, all CAR T cell therapy products are expected to be available, and methods of increasing accessibility and decreasing cost, such as outpatient administration, will be explored. Access to novel therapies is unfortunately a barrier to best practice or standard-of-care treatments that not only affect complete remission, overall survival, and disease-free survival rates, but may inadvertently increase risk of adverse events and increase cost of care. Access issues may also potentially influence the sequencing of these novel therapies based on geographic availability. Physicians without “quick” access to CAR T cell therapy may choose to prescribe a BiTE regimen at first relapse because it is easier to obtain through all the necessary channels than CAR T cell therapy, whereas a physician at an academic medical center may choose to pursue CAR T cell therapy at first relapse because the accessibility issues are not a barrier to care. How to best sequence these novel “high-tech” therapies is still under investigation. Hopefully, the discovery of “cleaner” BiTE and CAR T cell therapies with improved administration schedules and fewer potentially life-threatening adverse events will resolve current accessibility issues and no longer be a factor in subsequent treatment options.

Special thank you to Robert Mancini and Scott Robison for their contributions!

REFERENCES

- Garg, A., 2020. Community-based Cancer Care Quality and Expertise in a COVID-19 Era and Beyond. [online] Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32520792/ [Accessed 19 September 2022].

- Research C for DE and. FDA grants regular approval to blinatumomab and expands indication to include Philadelphia chromosome-positive B cell. FDA. Published online November 3, 2018. Accessed October 12, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-regular-approval-blinatumomab-and-expands-indication-include-philadelphia-chromosome [Accessed 19 September 2022].

- Duffy, C., Santana, V., Inaba, H., Jeha, S., Pauley, J., Sniderman, L., Ghara, N., Mushtaq, N., Narula, G., Bhakta, N., Rodriguez-Galindo, C. and Brandt, H., 2022. Evaluating blinatumomab implementation in low- and middleincome countries: a study protocol. [online] Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35690878/ [Accessed 28 September 2022].

- Buie, LW. Balancing the CAR T: Perspectives on Efficacy and Safety of CAR T-Cell Therapy in Hematologic Malignancies. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(13):S243-S252. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2021.88736

- Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) package insert. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp; May 2022

- Kelkar AH, Scheffer Cliff ER, Jacobson CA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy versus autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) for high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in first relapse. Journal of Clinical Oncology 40, no. 16_suppl (June 01, 2022) 7537-7537. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.7537

- FACT-JACIE Hematopoietic Cellular Therapy Accreditation Manual, Eighth Edition 8.2. https://fact.policytech.com/dotNet/documents/?docid=534&public=true. [Accessed 28 September 2022]

- Perica K, Curran KJ, Brentjens RJ, & Giralt SA. Building a CAR garage: Preparing for the delivery of commercial CAR T cell products at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2018;24, 1135-1141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.02.018

- Mahmoudjafari Z, Hawks KG, Hsieh AA, et al. American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Pharmacy Special Interest Group Survey on Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy Administrative, Logistic, and Toxicity Management Practices in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 25 (2019) 26-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.09.024

- FACT Immune Effector Cells Immune Effector Cells Accreditation Manual, First Edition 1.1. https://fact.policytech.com/dotNet/documents/?docid=238&public=true. [Accessed 28 September 2022]

- Manz CR, Porter DL, Bekelman JE. Innovation and Access at the Mercy of Payment Policy: The Future of Chimeric Antigen Receptor Therapies. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Feb 10;38(5):384-387. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.01691.

Reaching the Melting Point: My Time Transitioning from a Solid to a Liquid Tumor Pharmacist

Alison Palumbo, PharmD, MPH, BCOP

Clinical Oncology Pharmacist

Oregon Health and Science University

Working in the Community Hematology/Oncology Clinics at Oregon Health and Science University as a clinical oncology pharmacist, you see patients with all different types of cancers, but primarily the focus is solid tumors. This was the ideal practice setting for me as I enjoy being more of a cancer generalist than specialist, however I felt my hematology knowledge was starting to atrophy due lack of exposure. So, in April 2020 when the opportunity came up to cover a coworker’s maternity leave who works in inpatient hematology and bone marrow transplant (BMT), I was excited, if not a little apprehensive, to volunteer to cover her position. Here is what I learned from stepping in to fill her shoes:

When I first arrived on heme/BMT, I received a few days of training. At first it felt like riding a bike – my heme/BMT knowledge was coming back to me rapidly, and I started to feel comfortable enough to staff solo in the evenings. However, I quickly learned that while you may be able to retain a lot of information from residency (it had been 7 years for me), a lot can also change in 7 years. This is where I had to learn to get comfortable with being uncomfortable. This meant both accepting that I would not always have the answers readily available like I did in my role as a solid tumor pharmacist and remembering that taking a few steps back in a new role is perfectly normal. Taking a few steps back for me meant spending a lot of my downtime reading and getting caught up on updates in the heme/BMT world. I also learned to do more listening instead of talking so that I could learn from my peers.

I felt very fortunate to be surrounded by sharp, supportive colleagues who helped me navigate my way through my first few months on service. Some of these colleagues were even my former pharmacy residents who I had not worked with since they transitioned out of residency into their heme/BMT role. I was touched to see just how much these former residents had grown and come into their own as clinical pharmacists. Having this safe, supportive environment was essential for my success, and I am immensely grateful for the support they offered me.

By the end of my 6-month stretch covering heme/BMT, I felt comfortable with the subject matter and had established myself as a resource. I had developed strong relationships with the providers, nurses, and my pharmacist peers on the heme/BMT unit, and I was sad to leave them behind when it was time for me to return to my role at the Community Hematology/Oncology Clinics. Luckily, though this chapter of my life had closed, several months later I was once again given the opportunity to work inpatient heme/BMT to cover staffing shortages. While my primary position is solid tumor clinics, I now regularly staff heme/BMT once every 6 weeks. This provides a perfect balance for me between my interests, and I am grateful my job provides me with the flexibility to do both.

If you are faced with a similar opportunity to try out a new role or fill in for a peer, here are some words of advice:

- Be prepared to feel out of your depth and maybe a little overwhelmed. Oncology is a field that changes rapidly, so there may be a lot to catch up on. It is easy to feel down on yourself for not feeling as comfortable in your new role as you were in your last, but remember that comfortability takes time, and it is normal to feel growing pains in any kind of transition. Regardless of how it may feel, you belong where you are.

- Be ready for feedback, both positive and negative. For many of us, constructive feedback may not be something we are used to receiving when we have had a role for a long time, so it may feel uncomfortable at first. Just remember that feedback is how you improve and no one, even the most experienced of us, is free from error.

- Be grateful to your colleagues, but always respect boundaries. It may be helpful to ask your colleagues in what capacity they are willing to help before relying too heavily on them. For example, you could ask them how often you can reach out and in what capacity before assuming it is acceptable to text someone at home late at night or during off hours.

In summary, doing a complete 180 in your professional life is achievable! You will learn a lot and likely make some wonderful connections along the way. Wishing you the best of luck in whatever new opportunity life brings you!

“Survey Says....” - Reflections on the Oncology Pharmacy Workforce Survey and a Proposal for Action to Address the Great Migration

Zahra Mahmoudjafari, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Pharmacy Manager-Hem/BMT/Cellular Therapeutics

University of Kansas Cancer Center

Kansas City, KS

Alison M. Gulbis, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Pharmacy Manager

UT MD Anderson Cancer Center

Houston, TX

Kamakshi V. Rao, PharmD, BCOP, FASHP

Assistant Director of Pharmacy

UNC Medical Center

Professor of Clinical Education

UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy

Chapel Hill, NC

The idea of a “traditional” role in clinical pharmacy is being challenged by several factors. First, as therapies continue to develop, the work of a dedicated patient care pharmacist has become more complex. Additionally, the administrative workload that comes with the management of an ever-increasing cadre of therapy options results in pharmacists working harder to remain current with emerging data, while taking on greater amounts of tasks related to medication access, prior authorizations, site of care requirements, and increasing documentation obligations. Unfortunately, as the intricacies of the work burden rise, the time spent in activities that drive the meaningful reward of patient care is chipped away, leaving oncology pharmacists wanting for time to dedicate to patient care and other high-value activities.

Next, we must consider the career progression for a clinical pharmacist. After completing pharmacy school, clinical pharmacists complete 1-2 years of rigorous residency training, during which they are trained to pursue the esteemed triad of a clinical career – patient care, education, and scholarship – with the idea that this will set them up for a solid career trajectory. That said, many find that they have limited ability to advance their careers beyond the role of a “clinical pharmacist” in health systems settings unless they transition into a management role. Regardless of their pursuits or achievements in scholarship or education, the core work of patient care remains their 100% expectation without much incentive to do more. For those who want to develop skills outside of direct patient care, most institutions ask individuals to complete those activities outside of normal work hours. In this post-pandemic world, where personal priorities and a focus on well-being have come front and center, these expectations are challenging.

Last, it is important to recognize that the employment landscape available to trained clinical pharmacists is evolving rapidly. Pharmacists are sought after team members in many business sectors outside of traditional direct patient care models. Technology firms, pharmaceutical industries, continuing education companies, association management companies, and even start-ups see the value that experienced pharmacists bring to their business and are actively and intentionally recruiting them. Some level of attrition due to these developing opportunities must be not only expected but encouraged. For some pharmacists, career progression is best suited for new and evolving positions. That said, there has been a marked increase in “premature” attrition of hematology/oncology (H/O) pharmacists to these emerging roles. When attrition is seen as an “escape” or a direct patient care role is seen as a “stepping-stone”, we must ask ourselves what we can do to ensure that those who truly seek progression within the healthcare setting continue to find reward, value, advocacy, and advancement within that environment.

In response to the observation of these trends and the factors leading to colleagues across the H/O pharmacy space “migrating” to new roles, we aimed to bring objectivity to a subjective topic through the Oncology Workforce Survey. To date, it represents the most complete analysis evaluating job satisfaction and risk of attrition. The survey was completed nationally by over 600 H/O pharmacists in a variety of positions including academic medical centers (AMC), community medical centers (CMC), administration, academic and industry. Key survey findings included:1

- While 78% of respondents reported positive job satisfaction, 60% were still considered “at risk” for attrition or considering a “migration” to an alternative role.

- Job satisfaction is well-correlated with the amount of time spent in direct patient care (p=0.006).

- Higher degrees of clinical commitment are significantly associated with a decreased rate of attrition risk (p=0.0201).

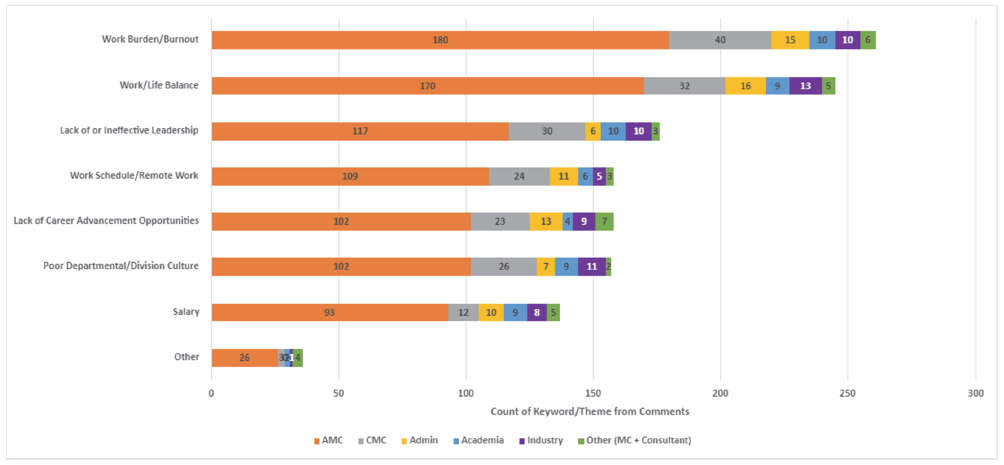

- Work burden/burnout, work/life balance, lack of or ineffective leadership, lack of advancement opportunities and work schedule were amongst the top 5 reasons for attrition. (Figure 1)

- Seventy-eight of the 102 (76.5%) respondents who had left clinical practice had greater than 5 years of experience in patient care prior to leaving.

While the survey was limited to H/O pharmacists as respondents, the trends and results are not unique to the oncology setting. On the contrary, these same results would likely be seen in nearly all areas of clinical pharmacy practice. Many of us know colleagues outside of oncology who face similar workplace challenges and have chosen to leave the clinical/patient care environment in pursuit of advancement or as an escape from an untenable work burden.2,3

One area of particular concern from our survey was the higher risk of attrition in H/O clinical pharmacists with more than 5 years of direct patient care experience. Pharmacists with this degree of experience are extremely valuable as clinical practice continues to increase in intricacy. Health systems rely on these pharmacists to help drive innovative change and to mentor new practitioners. If those with the muscle memory of clinical practice leave, it becomes significantly harder to commit to medium and long-range initiatives aimed at improving the care delivery experience.

Figure 1: Attrition Risk Factors by Work Environment

Our survey demonstrates that despite being “satisfied,” the majority were still open to other potential prospects. Satisfaction in the work environment may have much to do with the perceived personal worth and reward that comes from being directly involved with patient care, thus making satisfaction a blurry indicator of true retention. To drive deeper satisfaction and improve the likelihood that team members will stay, leaders must employ a multi-faceted approach to people and operational oversight, with a focus on 4 key factors:

Well-Being: Supporting the well-being of employees cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach, nor can it be something we ask team members to pursue on their own. Incentives and activities that resonate with one employee may not apply to another. Thus, leaders must have meaningful, individual dialogue with employees and teams to determine how to support and practice “well-being at work”. Having access to a variety of ways to support worker well-being is key. For some, flexible work schedules may be a satisfier, while for others, access to wellness days, or time and monetary support for activities of well-being may resonate more.

Recognition and Value: Responders to the survey commonly commented that their leadership and multidisciplinary colleagues such as physicians and nurses did not understand the level of training and commitment clinical pharmacists bring to the care environment, and did not adequately recognize or value the activities they were heavily vested in. Departments must build systems to truly recognize and appreciate their team members, not just for going “above and beyond”, but for doing the work they set out to do every day. When team members deliver high quality care, it deserves to be recognized. In addition, there needs to be meaningful value placed on those activities that have traditionally been seen as “extracurricular”. Activities such as publications, grant pursuits, speaking, teaching, or leadership in professional organizations are all things that drive and support the reputation not just of an individual, but of their department and their institution. Institutions and organizations should place visible value and incentive on these reputationally beneficial accomplishments.

Practice Model Evolution: As the work of clinical pharmacy has evolved, the models of practice need to evolve as well. Gone are the days when pharmacists could spend hours per day on rounds, hours per day in individual teaching, and “free time” to pursue professional endeavors. The growing complexity of healthcare decision making and delivery, the administrative burdens around access and authorizations, and the push for efficiency has become untenable. Residency program training has become unsustainable with the many accreditation requirements for both preceptors and residents. Leaders must embrace the challenge of developing and piloting never-before used practice models while balancing the need for productivity with the goal for employee satisfaction, well-being, engagement, and retention.

Workload Metrics: Lastly, work must be done on local and national levels to develop, advocate for, and endorse appropriate metrics and measures for clinical workload. Current models are antiquated and do not clearly bring clinical accountability to the value equation for the oncology clinical pharmacist. We also recommend routine opportunities for the team to provide meaningful feedback (i.e., retention interviews) and to be involved in efforts to improve processes. We must reassess what a safe pharmacist-to-patient ratio is, what true measures of impact and productivity are, and how to best advocate for pharmacists to be seen as core members of the healthcare delivery system, with a value statement commensurate with their impact.

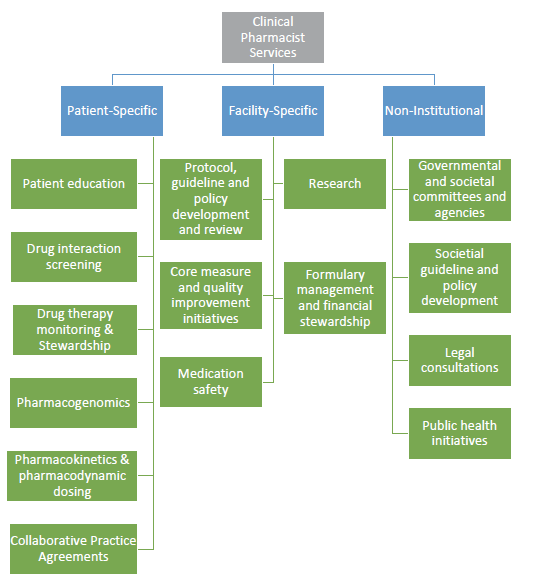

Pharmacists are involved in a variety of activities at the patient, facility, and non-institutional level, as described by Dunn et al (Figure 2).4 As the complexity of overall care has grown, the feasibility of a single pharmacist managing all of these activities in the course of a workday has become untenable without a thoughtful adjustment to how departments and institutions maintain high reliability in patient care.

Figure 2. Pharmacist activities at the patient, facility, and non-institutional level

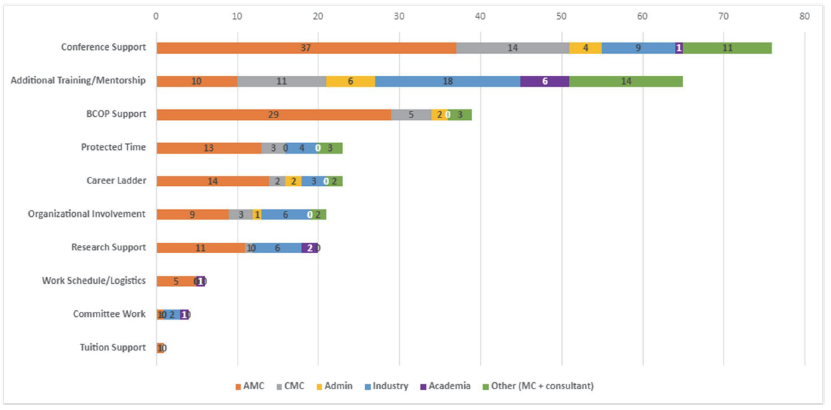

Figure 3: Emerging Opportunities to Retain the Hematology/Oncology Pharmacist Workforce

REFERENCES

- Rao K, Gulbis A, Mahmoudjafari Z. Assessment of attrition and retention factors in the oncology pharmacy workforce: results of the oncology pharmacy workforce survey. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022: 1-9. DOI: 10.1002/jac5.1693

- Rech MA, Jones GM, Naseman RW, Beavers C. Premature attrition of clinical pharmacists: call to attention, action and potential solutions.J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022;5:689-696. DOI: 10.1002/jac5.1631

- Lichvar A, Cohen E, Ingemi A, Fabbri K. Acts of attrition: The pressure on our clinical pharmacists, J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022; 5: 658-659. DOI:10.1002/jac5.1664

- Dunn SP, Birtcher KK, Beavers CJ, et al. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the care of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiology.2015;66(19):2129-2139. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.025

The Road Less Traveled: A Journey to Bring Quality Improvement Training to a Pharmacy Residency Program

Kathlene DeGregory, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Pharmacist, Stem Cell Transplant – UVA Health

Charlottesville, Virginia

Amy L. Morris, PharmD

Scientific Director of Oncology

Pharmacy Times Continuing Education

Choosing A Path

Since the time of the publication “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System“1 in 2000, healthcare has begun to shift focus to examine the systems we use to provide care and improvement of those systems. In 2001 the Institute of Medicine published “Crossing the Quality Chasm”2 to further describe how faulty system design and system performance are primary root causes for problems affecting patient safety, as well as how frontline staff are in key positions to affect change to those systems.3 At the University of Virginia (UVA), oncology pharmacists embarked on a journey to improve those systems and to educate others on the use of Quality Improvement (QI) tools.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) offers a quality-training program (QTP) to teach busy oncology clinicians how to improve the systems in which they work. ASCO QTP is a 6 month workshop designed to help interdisciplinary oncology teams develop, implement, and assess quality improvement changes within their organization. During the program, teams learn quality methodology, tools, and sustainability design as well as learning about teamwork, communication, and high reliability organizations. Three UVA oncology pharmacists, including the authors, attended ASCO QTP as part of interdisciplinary teams executing QI projects within the hematology/oncology service line. Final outcomes of UVA projects included reduction in length of stay and reduction in time to treatment of oncology patients. Due to the success of the UVA teams in executing QI initiatives, UVA hospital leadership approved tuition reimbursement to support additional employees attending the QTP program. We began to apply the tools and principles of QI into our daily practice, and as the value of this training became more apparent, we recognized the impact and importance of educating our fellow pharmacists as well as our pharmacy residents. The PGY2 oncology residency program began including their PGY2 resident as a team member in projects going through ASCO QTP but were unable to send the resident to the full training due to cost and timing of the program. So how does UVA ensure that our residents receive training in these valuable skills? Two oncology pharmacists decided we would just have to provide the training ourselves! In the fall of 2020, we embarked on a journey to bring this idea to fruition.

Into The Woods

Prior to 2020, all PGY1 and PGY2 residents at UVA were required to complete a quality improvement project (QIP) per ASHP standard Goal R2.2: “Demonstrate ability to conduct a quality improvement or research project in the advanced practice area”, but the QIP was often structured like a Medication Use Evaluation (MUE) or a research-style project with a quality outcome as the primary end point. Published QI tools were not utilized in an official capacity for these projects, and we were especially cognizant that R2.2.3 addressing data evaluation and sustainability could be improved by using validated quality analysis tools via continuous improvement cycles. We presented a proposal to the Residency Oversight Committee at UVA to restructure the content of QIPs, narrowing our scope to focus on the PGY1 program. We also included the PGY2 oncology resident due to our close involvement with the PGY2 oncology program. We developed a structure for education similar to what we had experienced in our own quality training via ASCO. This included conducting a QIP over six months using The Model for Improvement as a backbone and incorporating the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. In terms of our qualifications for leading this effort, each of us had completed the ASCO QTP, institution specific LEAN training, as well as online QI modules provided by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) open school. We designed our own training materials based on experiences with these organizations and review of the quality literature. To kick off, we conducted a preceptor development session outlining the new structure and the tools we would be using. All preceptors of PGY1 residents were asked to attend. We developed three, 1-hour didactic teaching sessions for the residents given at various intervals throughout the project timeline. We decided to serve as coaches for all projects to provide “in the moment teaching” as well as guidance and support for a new process for both residents and preceptors. The tools taught and utilized included process mapping, affinity sort, cause and effect diagramming, Pareto charts, priority matrix and statistical process control (SPC) charts. The projects were presented as posters at the Vizient meeting held in conjunction with the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) Mid-Year meeting.

Seeing The Forest for The Trees

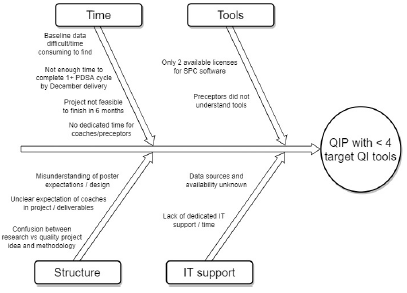

In our inaugural year, 6 PGY1 projects were completed. Of these, only 2 projects completed a full PDSA cycle within the 6-month time frame. Only 1 project included our target 4 QIP elements: Problem/aim statement, use of diagnostic tools (e.g., Pareto charts), analytical tools (e.g., statistical process control charts), and completion of 1 full PDSA cycle. The mean was 1.8 QI elements completed per project. In the true spirit of process improvement, we brainstormed potential barriers (Figure 1). The biggest areas for improvement revolved around time to educate both residents and preceptors on QI and time for residents to conduct the project.

Figure 1: Fishbone Diagram: Year 1 Quality Improvement Project

Changing Course

After brainstorming solutions to our identified barriers and prioritizing what was feasible and within our scope as preceptors, we made significant modifications to the QIP. Our QI committee joined with the existing research committee to create a longitudinal project committee. PGY1 residents chose either a research project or a QIP, both yearlong. Residents would attend all didactic teaching or presentation sessions for research and quality regardless of their project type, as both projects were equally important to our residency curriculum. Didactic sessions were updated annually based on previous resident feedback, including more detailed discussion on the use of diagnostic and analytical tools. In addition, a representative from the pharmacy informatics and technology (IT) team attended project proposal sessions to provide guidance on how to efficiently find baseline data. In order to spread the workload, we began training several preceptors to serve as coaches in the future, as coaching multiple QI projects during the first years was a significant workload increase for us. Due to some confusion over involvement of the QIP coach, we defined the role of the QIP coach in guidance documents provided to the residents at the beginning of the year. Expectations included the following: the QIP coach should be included in early meetings, should have regular updates regarding milestones for poster and platform presentations, and should review final posters and presentations for accuracy. An online resource folder with tip sheets for using QI tools and additional examples of posters and manuscripts was created. Unfortunately, finding dedicated precepting/coaching time was not something that could be implemented at this time.

In year 2, a total of 8 quality projects were selected by PGY1 residents. Quality coaches were assigned to each project to help guide each team and continue the “in the moment” teaching and expand upon the didactic teaching. All PGY2 residents were encouraged to use the PGY1 process and presentation forums, but it was only required for the PGY2 oncology resident. Residents presented their problem and aim statements and some of their diagnostic work in a group setting for shared learnings between all teams. Residents presented preliminary information in a poster format at ASHP Vizient in December, a platform presentation at University of North Carolina Research in Education and Practice Symposium (UNC REPS) in May, and a manuscript suitable for publication in June.

Into The Clearing

In our second year, 4 projects included all 4 target elements and we improved to a mean of 3.5 elements included per project. In addition to the improvement in using QI tools, 2 projects received special recognition. The PGY1 project entitled “Assessing Medication Access Barriers in Patients Living with HIV” received the top prize for the UVA Young Investigator Research Award and was invited for poster presentation at the 2022 National Ryan White Conference on HIV care and treatment. The PGY2 oncology project entitled “Utilization of UVA Health Pharmacies for Outpatient Prescription Dispensation in the Malignant Hematology and Thoracic Oncology Clinics” was awarded with a Quality Research Certificate at the 2022 HOPA Annual Conference.

Barriers identified from resident, preceptor and coaching feedback included ongoing preceptor confusion over how a research project was distinctly different from a QI project, as well lack of clarity in expectations for presenting QI tools in a poster format and a platform presentation. Time taken to obtain baseline data meant several teams suffered early delays in identifying outcome measures and implementing countermeasures.

The Steep Climb

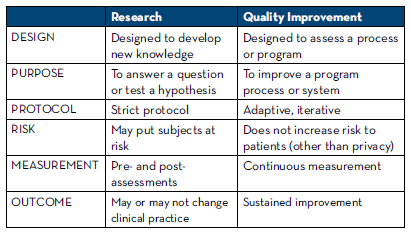

Based on year 2 feedback, our focus for improvement the current year involves investing in training for our preceptors in the use of QIP tools using existing educational avenues in order to free up coaching time and make precepting time more efficient. UVA Health was eligible to purchase an educational group subscription to IHI open school. The longitudinal project committee created two preceptor development tracks, one for research and one for QIP. Preceptors on the QIP track will complete the 5 online QI modules from IHI, as well as attend the in-house sessions. Additional focus will be on contrasting elements of QI with those of research to help preceptors and residents become comfortable with the distinction between them; Table 1 was included as part of this work.

The importance of accurate and relevant baseline data cannot be overstated. Ongoing discussions with IT leaders for assistance in obtaining baseline data in a timely manner are continuing. A mantra from QTP is “fail forward,” meaning learn from mistakes and failures to improve upon the system; one example included re-evaluating our own internal “measure” of success. Even though some projects from the previous year didn’t contain all four target elements, there was great value in the work the teams completed and those learnings were important to share. For example, the PGY2 oncology project focused on obtaining and understanding accurate baseline data, such that an improvement project could begin. Another team realized during the analysis of their diagnostic data that there were flaws in the process map and the process measure, revealing the team did not have a full understanding of the root problem and therefore they could not develop effective countermeasures. Rather than abandoning the work, they used this as an opportunity to illustrate the importance of working together as a team to understand the process as it currently exists, not a perceived ideal state.

Table 1: Distinguishing a Research vs Quality Improvement Project

The Map And Compass

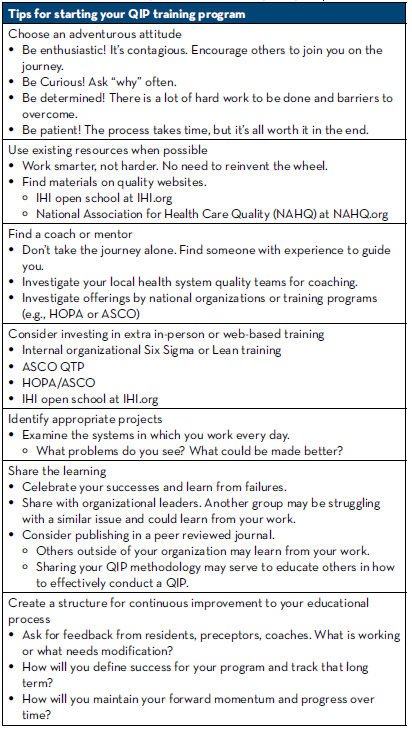

While our journey to educate pharmacy residents in the art of QIP is just getting started, we certainly have education to share regarding what it takes to start a program similar to this (Table 2).

Table 2: Tips for Starting Your QIP Training Program

As we continue to develop and improve our QIP program via PDSA cycles, we continue to look for external opportunities to grow as well as share our work. Our PGY2 oncology resident is currently attending the 6 month ASCO QTP / HOPA collaboration course, the first UVA resident to be funded to attend the program. We also relished the opportunity to write this newsletter and share our experience with those who may have started the journey or are wanting to take first steps but don’t know where to start. The road less traveled is full of surprises and difficult terrain, but the rewards and benefits are worth every step. Together we can change the face of health care, one process improvement at a time.

REFERENCES

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2000. PMID: 25077248.

- Institute of Medicine. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10027.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing, at the Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. PMID: 24983041.

- Al-Surimi K. Research versus Quality Improvement in Healthcare. Glob J Qual Saf Healthc. 2018;1(2): 25–27.

- Casarett D, Karlawish JHT, Sugarman J. Determining When Quality Improvement Initiatives Should Be Considered Research: Proposed Criteria and Potential Implications. JAMA. 2000;283(17):2275–2280.

- Langley GL, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance (2nd edition). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2009.

- How to Improve. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx

To Nelarabine or Not for Pediatric T-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Kristin Held Wheatley, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, Pediatric Oncology and Infectious Diseases Program Director, PGY1 Pharmacy Residency

Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) accounts for 15% of pediatric leukemias and patients are generally characterized by unfavorable clinical features including older age, male predominance, higher presenting leukocyte count, higher frequency of mediastinal mass and central nervous system (CNS) involvement at diagnosis.1,2 Survival has improved markedly with risk-directed therapy and has reached 80-85% though outcomes remain poor for patients who experience relapse.1

An agent with potential for targeted benefit in T-cell malignancies is the purine nucleoside analogue, nelarabine. Accumulation of intracellular deoxyguanosine (dGuo) triphosphate (dGTP) was noted to be specifically toxic to T-cells in patients with purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) deficiency. Arabinofuranosylguanine (ara-G) is a PNP-resistant dGuo analogue, but its clinical use was limited by solubility challenges. Nelarabine is available as a prodrug and is rapidly metabolized by adenosine deaminase to ara-G which is transported into leukemic cells and phosphorylated to the triphosphate form (ara-GTP), the main intracellular metabolite, where it accumulates and inhibits DNA synthesis. The selective T-cell toxicity demonstrated by nelarabine reflects inherently higher phosphorylation that occurs within T-cells compared with B-cells. Further, cytotoxicity occurs to a greater extent in T-lymphoblasts than in mature T-cells which may explain preferential utility in T-ALL compared to T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (T-LLy). Nelarabine has not been associated with toxicities commonly reported with more traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy; however, neurotoxicity is dose limiting and is thought to occur as a result of greater accumulation of ara-GTP within CNS tissue. CNS effects predominate with primarily reversible somnolence though seizures are also reported. Peripheral neuropathies may be severe, cumulative and gradually reversible and range from numbness and paresthesias to motor weakness and paralysis.3-6

Nelarabine received accelerated approval as a single agent in relapsed/refractory T-ALL and T-LLy following initial phase I and II studies. A phase I study enrolled 93 adult and pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies of which 66% of patients had T-cell malignancies. Doses ranged from 5 mg/kg to 75 mg/kg IV and responses were seen at all dose levels. Overall response rate (ORR) was reported as 31% in all disease subtypes with complete or partial response achieved in 54% of patients with T-ALL or T-LLy after one to two courses. Reversible toxicity was noted in 50% of pediatric patients with an onset of symptoms within 12 days of the start of therapy. No neurotoxicity was identified at a dose of 40 mg/kg within pediatric patients (roughly equivalent to 1200 mg/m2) and this dose was recommended for initial phase II trials.5 Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) P9673 enrolled 153 patients younger than 21 years with relapsed or refractory T-cell malignancies. Two dose de-escalations were required from the initial starting dose of 1200 mg/m2. Patients in first relapse experienced an ORR of 55% and tolerated 650 mg/m2 daily for five days. Grade 3 or 4 neurologic toxicities occurred in 18% of patients with 12% experiencing CNS toxicity and 9% peripheral nerve toxicity.6

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) added nelarabine, administered as five or six 5-day courses of 400 mg/m2 or 650 mg/m2, to an intensive modified Berlin-Frankfurt Münster (BFM) 86 regimen in children with newly diagnosed higher-risk T-ALL within AALL00P2. Five-year event-free survival (EFS) in slow early responders who received nelarabine was 69%, which was equivalent to rapid early responders who did not receive nelarabine. Grade 3 or 4 peripheral neuropathy occurred in 15% of patients who received nelarabine and in no patients who did not receive nelarabine (P = 0.203). Whereas, central neurotoxicity, excluding seizures, occurred in 4% of patients treated with nelarabine compared to 25% of patients who did not receive nelarabine (P = 0.019). Four patients treated with nelarabine experienced five seizure episodes – none occurred in conjunction with nelarabine administration. Nelarabine was reported as tolerable, safe and feasible when combined with intensive chemotherapy.7

The subsequent protocol, AALL0434, was a phase III trial evaluating nelarabine in patients with newly diagnosed intermediate risk (IR) or high risk (HR) T-ALL. Additional questions to be answered included whether cranial radiotherapy (CRT) could be minimized in low risk (LR) patients as well as the safety and efficacy of escalating dose (Capizzi) methotrexate (C-MTX) compared to high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX). AALL0434 enrolled 1562 patients and 5-year EFS and overall survival (OS) were 83.7% ± 1.1% and 89.5% ± 0.9%, respectively. All patients received a 28-day, prednisone-based, four-drug induction and were subsequently risk stratified as LR, IR, HR or induction failure. LR patients did not participate in the nelarabine randomization. Of note, 24% of patients were taken off protocol during induction prior to randomization at investigator discretion. Six hundred fifty-nine IR or HR patients were randomized to receive treatment with or without nelarabine given as six 5-day courses of 650 mg/m2 incorporated within consolidation (days 1-5 and 43-47), delayed intensification (days 29-33), and the first three maintenance cycles (days 29-33). All IR and HR patients received 12 Gy of prophylactic CRT. Patients randomized to nelarabine were reported to have superior disease-free survival (DFS) of 88.2% ± 2.4% compared to 82.1% ± 2.7% (P = 0.029) for those who did not receive nelarabine. OS was not statistically different between groups (90.3% ± 2.2% vs. 87.9% ± 2.3%, P = 0.168, respectively). Nelarabine was associated with a decrease in CNS relapses with 5-year cumulative incidence rates (isolated and combined) of 1.3% ± 0.6% in patients who received nelarabine (4 events) compared to 6.9% ± 1.4% in patients without nelarabine (23 events), P = 0.001. Day 29 minimal residual disease (MRD) < 0.1% was prognostic when compared to MRD ≥ 0.1% with or without nelarabine (92.3% ± 2.9% vs. 83.5% ± 3.9%, P = 0.01 compared to 89% ± 3.1% vs. 73.4% ± 4.3%, P = 0.0003). Peripheral motor and sensory neuropathy and central neurotoxicity rates were similar in the nelarabine and no nelarabine arms.8

The successor T-ALL study, AALL1231, incorporated bortezomib within a modified augmented BFM backbone. Notably, dexamethasone was used during induction and two additional doses of pegaspargase were added to eliminate CRT in the majority of patients. The modified induction was noted to result in improved end of induction MRD < 0.1% when compared with AALL0434 (69.6% [no bortezomib] and 72.2% [bortezomib] vs. 64.6%, respectively; P = 0.02). The 4-year EFS and OS were reported as 81.9% ± 1.5% and 87% ± 1.3%, respectively. The inferior OS when compared to AALL0434 was noted to be related to increased toxic deaths and poor outcomes of the very high risk (VHR) group. Induction mortality was higher in AALL1231 compared to AALL0434 (1.5% vs. 0.4%; P = 0.002) likely due to incorporation of dexamethasone as rates were similar to Associazione Italiana di Ematologia e Oncologia Pediatrica (AEIOP)-BFM ALL 2000.9,10 Though improvements in EFS and OS with bortezomib were specifically noted in patients with T-LLy, the adjustments made to therapy allowed elimination of CRT in more than 90% of patients.9

In the midst of completion and publication of the above North American trials, UKALL-2003, which enrolled between 2003 and 2011, demonstrated a 3-year EFS and OS for patients with T-cell phenotype of 86% ± 3.3% and 90% ± 2.8%, respectively. Notable differences in treatment included use of dexamethasone, restriction of CRT for overt CNS disease at presentation (CNS3) and utilization of C-MTX.10 Current treatment approaches for T-ALL in the United Kingdom reserve nelarabine for patients with poor initial response, MRD ≥ 5%, and/or relapsed disease.11,12

Addition of nelarabine comes at a cost including, at a minimum, 30 days of drug and extension of consolidation by 21 days. A recent commentary highlights the discrepancy in calculating the potential benefit based on the chemotherapy backbone. If the larger 6-percentage point advantage associated with the greater effect of nelarabine on the HD-MTX arm on AALL0434 was utilized to calculate a number needed to treat, 17 patients would need to be treated to avoid one relapse compared to 50 patients for the reportedly superior C-MTX arm.13, 14

Though nelarabine is a potentially beneficial intervention in certain patient groups, the available data is not conclusive and incorporation should be as part of rational decision making between the medical team, patients and families.

REFERENCES

- Teachey DT, Pui CH. Comparative features and outcomes between paediatric T-cell and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(3):e142-e154.

- Pocock R, Farah N, Richardson SE, Mansour MR. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2021;194(1):28-43.

- Kadia TM, Gandhi V. Nelarabine in the treatment of pediatric and adult patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017;10(1):1-8.

- Buie LW, Epstein SS, Lindley CM. Nelarabine: a novel purine antimetabolite antineoplastic agent. Clin Ther. 2007;29(9):1887-1899.

- Kurtzberg J, Ernst TJ, Keating MJ, et al. Phase I study of 506U78 administered on a consecutive 5-day schedule in children and adults with refractory hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3396-3403.

- Berg SL, Blaney SM, Devidas M, et al. Phase II study of nelarabine (compound 506U78) in children and young adults with refractory T-cell malignancies: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3376-3382.

- Dunsmore KP, Devidas M, Linda SB, et al. Pilot study of nelarabine in combination with intensive chemotherapy in high-risk T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2753-2759.

- Dunsmore KP, Winter SS, Devidas M, et al. Children’s Oncology Group AALL0434: a phase III randomized clinical trial testing nelarabine in newly diagnosed T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(28):3282-3293.

- Teachey DT, Devidas M, Wood BL, et al. Children’s Oncology Group trial AALL1231: a phase III clinical trial testing bortezomib in newly diagnosed T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(19):2106-2118.

- Möricke A, Zimmermann M, Valsecchi MG, et al. Dexamethasone vs prednisone in induction treatment of pediatric ALL: results of the randomized trial AIEOP-BFM ALL 2000. Blood. 2016;127(17):2101-2112.

- Vora A, Wade R, Mitchell CD, Goulden N, Richards S. Improved outcome for children and young adults with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL): results of the United Kingdom Medical Research Council (MRC) trial UKALL 2003 [abstract]. Blood. 2008;112(22). Abstract 908.

- Teachey DT, O’Connor D. How I treat newly diagnosed T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma in children. Blood. 2020;135(3):159-166.

- Agrawal AK, Michlitsch J, Golden C, et al. Nelarabine in pediatric and young adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia—clearly beneficial? J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(6):694.

- Gaynon PS, Parekh C. A new standard of care for childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68:e29238.

Maximizing Podcasts to Enhance Educational Needs in Oncology Pharmacy Practice

David M. Hughes, PharmD, BCOP

Director, Field Medical (Oncology) Pfizer

New York, NY

Acknowledgement: Jason Mordino, Bernard Marini, Anthony Perissinotti, and John Bossaer for their review of this material.

Podcasting has become increasingly popular in recent years. However, many early, and even seasoned, pharmacists do not maximize the true potential that podcasts may offer. While there has been a strain on many pharmacists that has been heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic, there remains a need to continue to develop both clinically and professionally with limited time. Furthermore, balancing quality of life becomes incredibly challenging. Hence, podcasts are one way, if used efficiently, to fill many of these gaps to help promote balance and enhance skillsets. These are 5 ways to fulfill practice gaps without a demanding time commitment!

1. Enhancing preceptor development

Preceptor development is a fundamental element of pharmacy practice from advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) to core postgraduate program rotations. It is critical for learners to learn from seasoned preceptors and preceptors have an obligation to further refine skillsets and learn from positive and negative experiences. However, in pharmacy practice, there is lack of prioritization of preceptor development due to time demands of operational and clinical needs of health systems and organizations. Longer, traditional, didactic lectures fail to address the need and pharmacists should seek alternative methods to fulfill this requirement. Precept Responsibly is a new podcast that interviews preceptors across the country and discusses unique challenges in practice. These shorter episodes can be a lighter listen at the end of the day that does not involve pre-reads or proactive preparation. Tune into episodes to hear about ways to integrate learners and advance in your professional career. Not only are they a dynamic listen but also can help fulfill preceptor requirements at your respective institution!

2. Specializing in focus areas of oncology pharmacy practice

Every resident strives to want to know everything there is about oncology and be able to recite primary literature. However, they quickly become self-defeated due to a fast-changing oncology landscape. Some podcasts can enhance knowledge by focusing in on a certain area of oncology pharmacy practice. WolverHeme is a podcast dedicated to those with a hematology focus. Seasoned preceptors will discuss new, controversial data, novel therapies, and new research areas in hematology. Therefore, if you want to grow in bone marrow transplant or malignant hematology, you can listen in to not only learn about the landscape but learn about academic ways to appraise new literature. This podcast makes literature not so intimidating and gives perspective on strong clinical, oncology presence at an academic medical center. Find podcasts like this one in your area of focus. If you focus on breast cancer, there are likely podcasts based on breast cancer research. However, remember, the goal is not to memorize or recite the knowledge, but take seasoned practitioners’ perspective and fine tune your approach!

3. Following FDA updates, new drug approvals, and basics of oncology practice

Oncology drug approvals seem like they occur on a weekly basis. If a new drug is not approved, a drug that is already approved, gets an expanded oncologic indication. Podcasts that offer a more frequent cadence, that address this can help keep oncology pharmacists up to date in real time. OncoPharm is a podcast devoted to recent publications and use of medications as it relates to treating patients with cancer. The weekly nature of the podcast, in short 20-minute segments, makes this an easy listen on a short commute to work every Friday and gives you a perspective on the application to clinical practice. Additionally, periodic episodes will feature fundamentals of oncology practice and focus on basic principles for those new to oncology practice or those starting residency. A second podcast featuring key drug approvals is Drug Information Soundcast in Clinical Oncology (DISCO). This podcast is led by the FDA and provides information on emerging safety data for cancer treatments, current topics in development, and new approvals in oncology. Staying up to date on approvals is one way to always stay ahead of the game to make sure you know how the field is changing!

4. Appraising scientific literature and understanding health policy in oncology care

Being new to oncology practice, it is easy to get caught up in media hype of press releases of larger clinical trials, oftentimes coupled with an FDA drug approval. However, part of differentiating yourself early in your pharmacy career is to look beyond the “flashy” titles and evaluate literature and understand how decisions are made from a regulatory perspective. Plenary Session offers insightful perspective on oncology drug approvals and an analytical perspective on the strength of data supporting it. While many of the topics in this podcast can be controversial, it is critical to think independently and formulate your own decisions that will affect your patient practice. This is just one example of many podcasts that appraise literature and finding and using them to hear new perspectives can be helpful for future analyzing.

5. Post-conference coverage

Within oncology, there are too many conferences to count each year. Some bigger ones, like ASCO and ASH have enormous amounts of data and it can be overwhelming and time consuming to sift through key abstracts. Podcasts can offer conference summaries and/or perspectives on platform or high impact presentations. Occasionally, hosts on podcasts will invite the presenters to do a de-brief on the presentation. Not only do you gain the knowledge of what was presented but also get to listen in to the perspective of the investigator that completed the trial. Even in some of the podcast examples cited above, many of them incorporate post-conference material to make it easier and digestible for their listeners!

Clinical practice can be overwhelming and time consuming. However, it is the responsibility of us, as practitioners, to further enhance our knowledge in the oncology field and in the profession, regardless of practice area. Podcasts offer a streamlined way to supplement more traditional methods of learning. Remember, while helpful, podcasts should not replace other methods. If you are doing a journal club, do not go out and find a podcast that streams a journal club solely that you recite and use. Read the article, come up with your own thought process, then listen to the podcast episode. It will allow you to self-reflect and appreciate what you analyzed and how you could view the literature differently. And finally, a caution: many podcasts are based on perspective/opinions of the host. Make sure the podcasts you listen to are well supported by evidence-based practices. Podcasts are the modernized way to learn and maximizing them will help refine you clinically and professionally.

Additional Resources:

Precept Responsibly

- Co-Hosts:

Jason Mordino, PharmD, BCCCP

David Hughes, PharmD, BCOP - Producer:

Spencer Sutton, PharmD - https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/precept-responsibly/id1629149808

WolverHeme

- Co-Hosts:

Bernard Marini, PharmD, BCOP

Anthony Perissinotti, PharmD, BCOP - https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/wolverheme-happy-hour/id1615110832

Oncopharm

- Host:

John Bossaer, PharmD, BCOP - https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/oncopharm/id1305345744

Drug Information Soundcast in Clinical Oncology (DISCO)

- Host:

FDA-led - https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/fda-drug-information-soundcast-in-clinical-oncology-d-i-s-c-o/id1237857198

Plenary Session

- Host: Vinay Prasad, MD

- https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/plenary-session/id1429998903

Feature: Lu-177-PSMA-617 for the Treatment of Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer

Bryan Fitzgerald, PharmD, BCOP

Oncology Clinical Pharmacy Specialist

University of Rochester Medical Center

Rochester, NY

Background

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in males in the United States, with an estimated 268,490 new cases diagnosed and 34,500 deaths in 2022.1-2 In general, most men diagnosed do not die from their prostate cancer, with favorable 5-year relative survival rates of 96.8%.1-2 However, presentation ranges from localized disease to widespread metastatic disease, with prognoses and treatment considerations varying considerably.

Treatment for advanced and metastatic prostate cancer includes the use of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) to achieve castrate levels of testosterone of less than 50 ng/dL. Patients with metastatic disease which progresses despite these castrate levels of testosterone are classified as having metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Generalizing prognosis for patients with mCRPC can be difficult, as this population is heterogeneous and various disease characteristics and risk factors may contribute to the overall survival picture.

For the treatment of mCRPC, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) preferentially recommends abiraterone, enzalutamide, and docetaxel, in no specific order.3 After exposure to novel hormonal therapy (NHT, e.g. abiraterone or enzalutamide), the NCCN recommends treatment with docetaxel. Conversely, after prior docetaxel therapy, treatment with abiraterone or enzalutamide are recommended.

After progression on both NHT and docetaxel, treatment options for mCRPC are somewhat limited. Current recommendations include agents such as cabazitaxel, radium-223, poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (olaparib, rucaparib), and pembrolizumab; however, many of these agents are recommended only for select patients with treatment criteria that are not applicable to the entire mCRPC population.3 Radium-223 is indicated for mCRPC patients with symptomatic bone-only metastases; therefore, any patient with visceral metastases would not be considered a candidate for this agent. PARP inhibitors play a role in treatment if tumor cells harbor DNA repair pathway mutations (i.e. BRCA mutation), which may only be present in up to 30% of patients.4 Pembrolizumab is only recommended for patients with particular markers of genomic instability.3 Only cabazitaxel has an indication for all patients with mCRPC whose disease progressed on docetaxel, without specific disease-related constraints.

Lutetium-177 vipivotide tetraxetan (Lu-177-PSMA-617) is the most recent novel agent approved for the treatment of mCRPC, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in March 2022. It is indicated for the treatment of patients with prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-positive mCRPC who have received novel hormonal therapy and taxane-based chemotherapy.5 By offering a new treatment option for these patients, the approval of Lu-177-PSMA-617 potentially changes the treatment landscape for mCRPC.

PSMA

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), also called glutamate carboxypeptidase II, is a transmembrane protein present on the cell surfaces in various tissue types, including the prostate, salivary glands, proximal renal tubules, and small intestine.6 Specifically, PSMA expression is 100 to 1000 times greater on prostate cancer cells than normal prostate cells.7 Clinically, PSMA overexpression has been associated as a poor prognostic factor in patients with prostate cancer.8

Because of its high levels of expression on prostate cancer cells, PSMA has been investigated as a tumor-specific target. Currently, PSMA is the target for two radioactive diagnostic agents utilized for prostate cancer imaging via PSMA PET, gallium-68 (Ga-68) PSMA-11 and fluorine-18 (F-18) piflufolastat PSMA.3 Compared with conventional imaging, PSMA PET has the benefit of providing increased sensitivity and specificity of detecting micrometastatic disease and has considerably changed the imaging landscape of prostate cancer.3 Lu-177-PSMA-617 is a radiopharmaceutical consisting of PSMA-617, a PSMA-binding ligand, conjugated with radioactive lutetium-177 (Lu-177). Upon binding to PSMA on the surface of prostate cancer cells, the radioligand-receptor complex is internalized, allowing direct, targeted delivery of the radioligand.8 Specifically, Lu-177-PSMA-617 emits beta-radiation within the PSMA-positive cells along with the surrounding microenvironment, resulting in DNA damage and cell death.8-9

VISION Trial

The efficacy and safety of Lu-177-PSMA-617 was shown in the VISION trial, an open-label, international, phase 3 trial in patients with previously-treated mCRPC.9 To enroll in the trial, patients had to have proven mCRPC with disease progression after treatment with at least one taxane (docetaxel or cabazitaxel) and at least oneandrogen receptor pathway inhibitor (abiraterone or enzalutamide). Additionally, patients had to have at least one PSMA-positive metastatic lesion with no dominant PSMA-negative lesion(s) determined with gallium-68-PSMA-11 imaging.

In a 2:1 fashion, patients were randomized to receive Lu-177-PSMA-617 plus standard care or standard care alone. Standard care agents included abiraterone, enzalutamide, bisphosphonates, denosumab, radiation therapy, or glucocorticoids. Patients could not concurrently receive radium-223, immunotherapy, cytotoxic chemotherapy, or investigational drugs. The authors report that the use of these agents were prohibited because their safety in combination with Lu-177-PSMA-617 has not been demonstrated. Although 831 patients were initially randomized, only 581 patients were included in the analysis group (385 in the investigational arm and 196 in the control arm) after “enhanced trial-site education measures were implemented.” Lu-177-PSMA-617 was administered intravenously at a dose of 7.4 GBq (200 mCi) every six weeks for four cycles, but could be given for a total of six cycles at physician discretion. Patients continued treatment until disease progression on imaging was documented, unacceptable toxicities occurred, a perceived lack of clinical benefit, or initiation of a prohibited treatment agent.

The two primary outcomes were imaging-based progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Imaging-based PFS was defined as time from randomization to disease progression (as determined by independent central review) or death. OS was defined as time from randomization to death. Secondary outcomes included objective response rate (ORR), disease control, time to first symptomatic skeletal event or death, safety, health-related quality of life, pain, and PSA response.

With a median follow-up of 20.3 months in the Lu-177-PSMA-617 group and 19.8 months in the control group, patients receiving Lu-177-PSMA-617 had a significantly longer median imaging-based PFS of 8.7 months vs 3.4 months (HR 0.40; 99.2% CI 0.29 – 0.57; p < 0.001). Median OS was also longer in the Lu-177-PSMA-617 group: 15.3 months vs 11.3 months (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.52 – 0.74; p < 0.001). Secondary outcomes favored Lu-177-PSMA-617, with an extended time to symptomatic skeletal events, longer time to pain progression, and decreased PSA levels.

In the VISION trial, the most common adverse events of Lu-177-PSMA-617 included fatigue (43%), dry mouth (39%), nausea (35%), and anemia (32%). Patients in the Lu-177-PSMA-617 group had a higher incidence of grade 3 or higher events, 53% vs 38%. Of note, 12% of patients discontinued Lu-177-PSMA-617 due to adverse events and 16% of patients had an adverse event leading to a dose interruption.9

Considerations