“Survey Says....” - Reflections on the Oncology Pharmacy Workforce Survey and a Proposal for Action to Address the Great Migration

Zahra Mahmoudjafari, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Pharmacy Manager-Hem/BMT/Cellular Therapeutics

University of Kansas Cancer Center

Kansas City, KS

Alison M. Gulbis, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Pharmacy Manager

UT MD Anderson Cancer Center

Houston, TX

Kamakshi V. Rao, PharmD, BCOP, FASHP

Assistant Director of Pharmacy

UNC Medical Center

Professor of Clinical Education

UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy

Chapel Hill, NC

The idea of a “traditional” role in clinical pharmacy is being challenged by several factors. First, as therapies continue to develop, the work of a dedicated patient care pharmacist has become more complex. Additionally, the administrative workload that comes with the management of an ever-increasing cadre of therapy options results in pharmacists working harder to remain current with emerging data, while taking on greater amounts of tasks related to medication access, prior authorizations, site of care requirements, and increasing documentation obligations. Unfortunately, as the intricacies of the work burden rise, the time spent in activities that drive the meaningful reward of patient care is chipped away, leaving oncology pharmacists wanting for time to dedicate to patient care and other high-value activities.

Next, we must consider the career progression for a clinical pharmacist. After completing pharmacy school, clinical pharmacists complete 1-2 years of rigorous residency training, during which they are trained to pursue the esteemed triad of a clinical career – patient care, education, and scholarship – with the idea that this will set them up for a solid career trajectory. That said, many find that they have limited ability to advance their careers beyond the role of a “clinical pharmacist” in health systems settings unless they transition into a management role. Regardless of their pursuits or achievements in scholarship or education, the core work of patient care remains their 100% expectation without much incentive to do more. For those who want to develop skills outside of direct patient care, most institutions ask individuals to complete those activities outside of normal work hours. In this post-pandemic world, where personal priorities and a focus on well-being have come front and center, these expectations are challenging.

Last, it is important to recognize that the employment landscape available to trained clinical pharmacists is evolving rapidly. Pharmacists are sought after team members in many business sectors outside of traditional direct patient care models. Technology firms, pharmaceutical industries, continuing education companies, association management companies, and even start-ups see the value that experienced pharmacists bring to their business and are actively and intentionally recruiting them. Some level of attrition due to these developing opportunities must be not only expected but encouraged. For some pharmacists, career progression is best suited for new and evolving positions. That said, there has been a marked increase in “premature” attrition of hematology/oncology (H/O) pharmacists to these emerging roles. When attrition is seen as an “escape” or a direct patient care role is seen as a “stepping-stone”, we must ask ourselves what we can do to ensure that those who truly seek progression within the healthcare setting continue to find reward, value, advocacy, and advancement within that environment.

In response to the observation of these trends and the factors leading to colleagues across the H/O pharmacy space “migrating” to new roles, we aimed to bring objectivity to a subjective topic through the Oncology Workforce Survey. To date, it represents the most complete analysis evaluating job satisfaction and risk of attrition. The survey was completed nationally by over 600 H/O pharmacists in a variety of positions including academic medical centers (AMC), community medical centers (CMC), administration, academic and industry. Key survey findings included:1

- While 78% of respondents reported positive job satisfaction, 60% were still considered “at risk” for attrition or considering a “migration” to an alternative role.

- Job satisfaction is well-correlated with the amount of time spent in direct patient care (p=0.006).

- Higher degrees of clinical commitment are significantly associated with a decreased rate of attrition risk (p=0.0201).

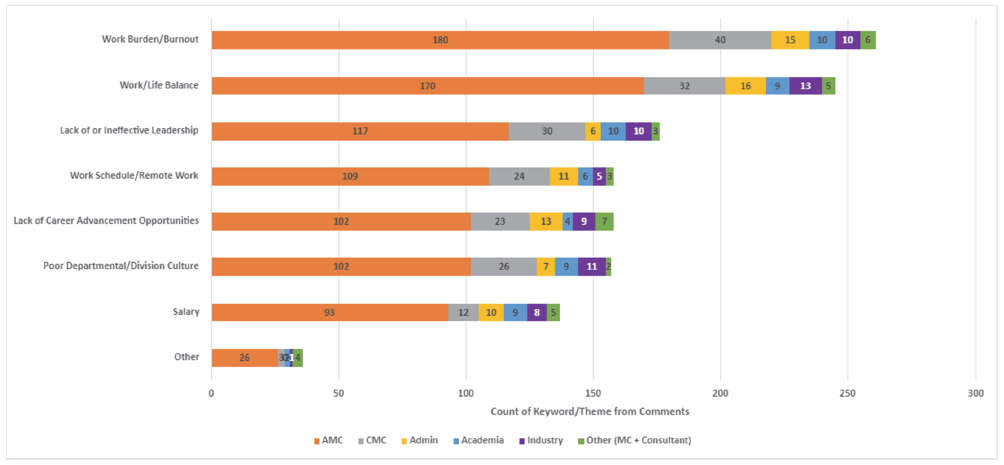

- Work burden/burnout, work/life balance, lack of or ineffective leadership, lack of advancement opportunities and work schedule were amongst the top 5 reasons for attrition. (Figure 1)

- Seventy-eight of the 102 (76.5%) respondents who had left clinical practice had greater than 5 years of experience in patient care prior to leaving.

While the survey was limited to H/O pharmacists as respondents, the trends and results are not unique to the oncology setting. On the contrary, these same results would likely be seen in nearly all areas of clinical pharmacy practice. Many of us know colleagues outside of oncology who face similar workplace challenges and have chosen to leave the clinical/patient care environment in pursuit of advancement or as an escape from an untenable work burden.2,3

One area of particular concern from our survey was the higher risk of attrition in H/O clinical pharmacists with more than 5 years of direct patient care experience. Pharmacists with this degree of experience are extremely valuable as clinical practice continues to increase in intricacy. Health systems rely on these pharmacists to help drive innovative change and to mentor new practitioners. If those with the muscle memory of clinical practice leave, it becomes significantly harder to commit to medium and long-range initiatives aimed at improving the care delivery experience.

Figure 1: Attrition Risk Factors by Work Environment

Our survey demonstrates that despite being “satisfied,” the majority were still open to other potential prospects. Satisfaction in the work environment may have much to do with the perceived personal worth and reward that comes from being directly involved with patient care, thus making satisfaction a blurry indicator of true retention. To drive deeper satisfaction and improve the likelihood that team members will stay, leaders must employ a multi-faceted approach to people and operational oversight, with a focus on 4 key factors:

Well-Being: Supporting the well-being of employees cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach, nor can it be something we ask team members to pursue on their own. Incentives and activities that resonate with one employee may not apply to another. Thus, leaders must have meaningful, individual dialogue with employees and teams to determine how to support and practice “well-being at work”. Having access to a variety of ways to support worker well-being is key. For some, flexible work schedules may be a satisfier, while for others, access to wellness days, or time and monetary support for activities of well-being may resonate more.

Recognition and Value: Responders to the survey commonly commented that their leadership and multidisciplinary colleagues such as physicians and nurses did not understand the level of training and commitment clinical pharmacists bring to the care environment, and did not adequately recognize or value the activities they were heavily vested in. Departments must build systems to truly recognize and appreciate their team members, not just for going “above and beyond”, but for doing the work they set out to do every day. When team members deliver high quality care, it deserves to be recognized. In addition, there needs to be meaningful value placed on those activities that have traditionally been seen as “extracurricular”. Activities such as publications, grant pursuits, speaking, teaching, or leadership in professional organizations are all things that drive and support the reputation not just of an individual, but of their department and their institution. Institutions and organizations should place visible value and incentive on these reputationally beneficial accomplishments.

Practice Model Evolution: As the work of clinical pharmacy has evolved, the models of practice need to evolve as well. Gone are the days when pharmacists could spend hours per day on rounds, hours per day in individual teaching, and “free time” to pursue professional endeavors. The growing complexity of healthcare decision making and delivery, the administrative burdens around access and authorizations, and the push for efficiency has become untenable. Residency program training has become unsustainable with the many accreditation requirements for both preceptors and residents. Leaders must embrace the challenge of developing and piloting never-before used practice models while balancing the need for productivity with the goal for employee satisfaction, well-being, engagement, and retention.

Workload Metrics: Lastly, work must be done on local and national levels to develop, advocate for, and endorse appropriate metrics and measures for clinical workload. Current models are antiquated and do not clearly bring clinical accountability to the value equation for the oncology clinical pharmacist. We also recommend routine opportunities for the team to provide meaningful feedback (i.e., retention interviews) and to be involved in efforts to improve processes. We must reassess what a safe pharmacist-to-patient ratio is, what true measures of impact and productivity are, and how to best advocate for pharmacists to be seen as core members of the healthcare delivery system, with a value statement commensurate with their impact.

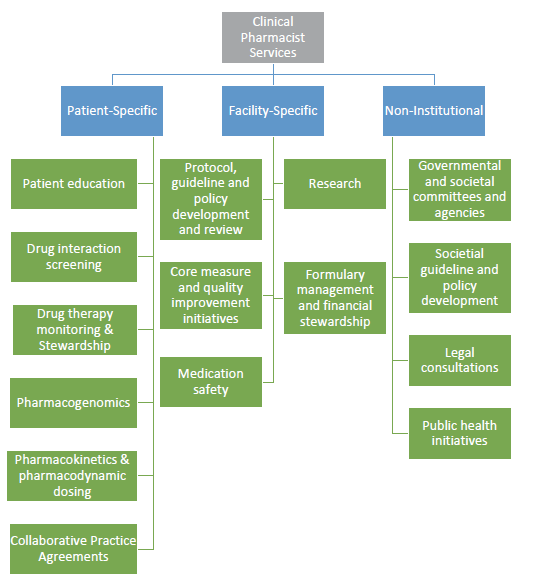

Pharmacists are involved in a variety of activities at the patient, facility, and non-institutional level, as described by Dunn et al (Figure 2).4 As the complexity of overall care has grown, the feasibility of a single pharmacist managing all of these activities in the course of a workday has become untenable without a thoughtful adjustment to how departments and institutions maintain high reliability in patient care.

Figure 2. Pharmacist activities at the patient, facility, and non-institutional level

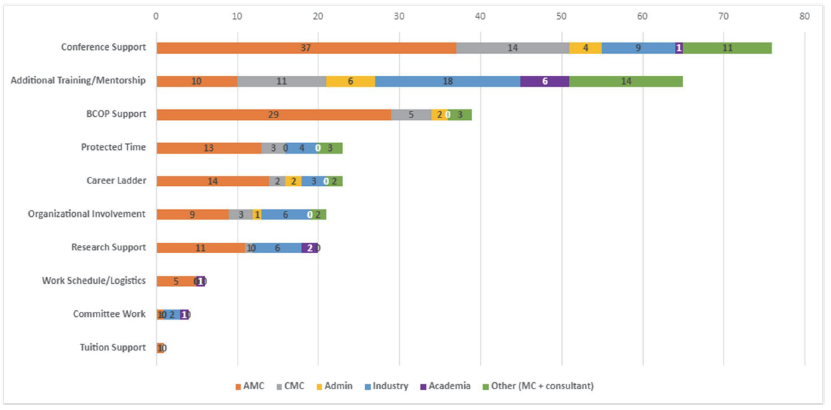

Figure 3: Emerging Opportunities to Retain the Hematology/Oncology Pharmacist Workforce

REFERENCES

- Rao K, Gulbis A, Mahmoudjafari Z. Assessment of attrition and retention factors in the oncology pharmacy workforce: results of the oncology pharmacy workforce survey. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022: 1-9. DOI: 10.1002/jac5.1693

- Rech MA, Jones GM, Naseman RW, Beavers C. Premature attrition of clinical pharmacists: call to attention, action and potential solutions.J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022;5:689-696. DOI: 10.1002/jac5.1631

- Lichvar A, Cohen E, Ingemi A, Fabbri K. Acts of attrition: The pressure on our clinical pharmacists, J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022; 5: 658-659. DOI:10.1002/jac5.1664

- Dunn SP, Birtcher KK, Beavers CJ, et al. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the care of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiology.2015;66(19):2129-2139. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.025