HOPA Publications Committee

Christan M. Thomas, PharmD BCOP, Editor

Renee McAlister, PharmD BCOP, Associate Editor

Lisa Cordes, PharmD BCOP BCACP, Associate Editor

Andrea Clarke, PharmD BCOP

Jeff Engle, PharmD MS

Ashley E. Glode, PharmD BCOP

Sidney V. Keisner, PharmD BCOP

Chung-Shien Lee, PharmD BCOP BCPS

Heather N. Moore, PharmD BCOP

Gregory Sneed, PharmD

Diana Tamer, PharmD BCOP

Jennifer Zhao, PharmD BCOP

View PDF of HOPA News, Vol. 18, no. 1

Board Update: Spring Forward

David DeRemer, PharmD BCOP FCCP FHOPA

HOPA President (2020–2021)

Clinical Associate Professor, University of Florida College of Pharmacy

Assistant Director, Experimental Therapeutics, University of Florida Health Cancer Center

Gainesville, FL

John F. Kennedy profoundly wrote, “Change is the law of life, and those who look only to the past and present are certain to miss the future.” As we look back over the past year, COVID-19 has significantly impacted our daily lives and has led to substantial changes that may persist well into our futures.

In this issue of HOPA News, member contributors share their experiences and insight on how COVID-19 has disrupted pharmacy practices. Among other changes, telehealth services emerged in the management of oral chemotherapy, as discussed in the cover story.

The need to adapt has led to substantial change for many within our organization. Is the practice transformation toward telehealth cemented in our professional futures? What other changes may persist long after the pandemic? For additional insight, I encourage you to attend our Annual Conference 2021 (AC21) where there are Clinical Pearls dedicated to this topic.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

As a society, the narrative has shifted from diversity and inclusion toward equity; as an organization, we are committed to adapting to these changes. HOPA continues to be engaged with other pharmacy organizations within Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP) to prioritize strategies to combat racial injustice.

In January, all HOPA Board members and staff virtually attended a DEI retreat led by Priya Jindal from Nextpat. I know I speak for everyone when I say this experience was valuable for us as individuals and collectively as a cohesive group. The retreat incorporated a comprehensive review of the DEI membership survey that you completed (n=168 member responses). Thank you for your participation in this important assessment. I look forward to presenting this data, along with our organizational activities of the past year, during AC21.

There are several other opportunities to participate in DEI initiatives at AC21, too. There will be a panel discussion on health disparities in cancer care during one of the BCOP sessions and the John G. Kuhn Keynote Lecture is entitled, “Dismantling Structural Racism in Pharmacy.” The keynote will be given by Lakesha M. Butler, PharmD, BCPS, Clinical Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice; Diversity and Inclusion Coordinator, Southern Illinois University College of Pharmacy.

Dr. Butler was selected by our Annual Conference Planning Committee based on her national reputation. She is the immediate Past-President of the National Pharmaceutical Association (NPhA) and a national leader in promoting diversity initiatives.

Annual Conference 2021

By now, many of us are experiencing virtual fatigue and with the conference just weeks away, I wanted to highlight how our online meeting will come to life.

You will still get the historically excellent hematology/oncology education and professional networking you’ve come to expect. And, there will be plenty of industry collaboration and member research, along with social connectivity – in every sense of the word.

A 3D virtual platform called 6Connex will foster engagement and minimize virtual fatigue. With gamification, social networking and connection, and real-time meeting analytics, we hope to create the same environment Portland would have provided (minus the rain).

I’m personally very excited about the Patient Advocacy Town Hall, which will be facilitated by the Patient Outreach Committee led by Jennifer Powers and James Connelly. Special acknowledgement goes out to everyone making the patient town hall possible. I look forward to seeing my “old” professional colleagues, as well as many of our new trainees, clinical specialists, administrators, and industry partners.

Transitioning to a HOPA Ambassador

This is my final HOPA News Board Update as President. It has been an honor to serve this wonderful organization. While serving in this capacity during a year when we changed management companies (during a pandemic), wasn’t always easy, I do feel fortunate.

I have been surrounded by a great team, including the HOPA Board, staff, committees, and many members whose support I have felt and appreciated. I want to personally thank outgoing Board members, Susie Liewer, Sally Barbour, and Jeremy Whalen for their insight, activity, and commitment to our organization.

Soon, I will assume the role of Past-President but specifically will engage as a HOPA Ambassador. I am looking forward to this new role and will continue to strive to advance our organizational mission, advocate for cancer patients, engage in committee activities, mentor members as needed, and most importantly promote positivity.

At the Annual Conference, Larry Buie will assume the role of HOPA President and I am eagerly looking forward to his leadership. For now, your “virtual” President is signing off.

Launching an Oral Chemotherapy Telehealth Clinic Using the TAMER Model

Diana Tamer, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Assistant Professor – University of Missouri Kansas City School of Pharmacy, Missouri

Hematology/Oncology Pharmacy Specialist – Advent Health Cancer Center

Shawnee Mission, KS

Background

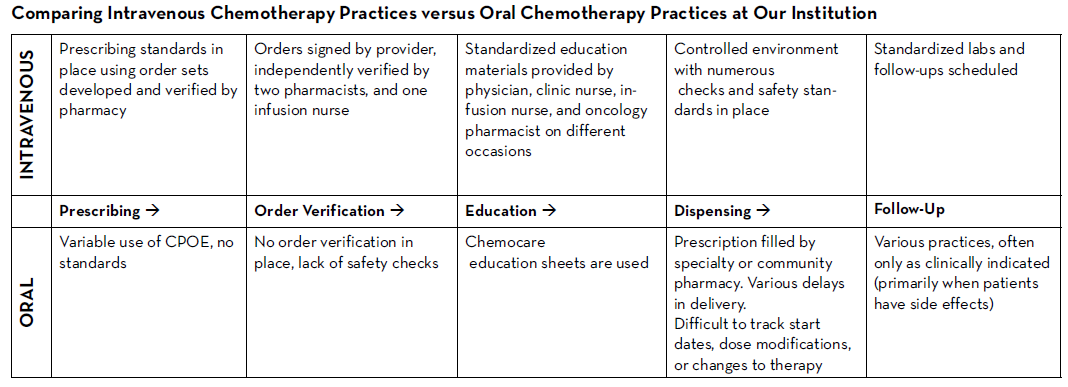

Oral chemotherapy—also known as oral oncolytics—has been available for nearly seven decades.1 Today, up to 35% of new oncologic agents in the pipeline consist of oral formulations.1 As of December 18, 2020, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had 56 treatment approvals for cancer indications; of which 23 were oral chemotherapy.2

There are many established safety and quality standards for intravenous cancer treatments. Patients treated with intravenous cancer therapies at a cancer center have scheduled visits and are closely monitored. Conversely, national guidelines and workflows for oral cancer therapies vary immensely based on the institution, and continue to be a work in progress. Oral chemotherapy offers cancer patients more flexibility, less disruption to their daily lives, and more autonomy.3 Nevertheless, the effectiveness of these therapies depends greatly on patients’ adherence. Common barriers to patient adherence include complex administration instructions, limited knowledge about the therapy and adverse events, low health literacy, and financial toxicity.4

As these therapies become widely prescribed, it is vital to identify current oral chemotherapy practices at local institutions and learn from successful programs and best practices published by national guiding bodies. Developing a workflow to manage patients on oral chemotherapy requires multidisciplinary collaborative efforts between pharmacists, physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, social workers, and financial navigators. These efforts require significant staff time to assure patient access to medication, adequate education, proper adherence, and adverse event monitoring, as well as side effect management.

The biggest challenges to implementing oral chemotherapy services are monetary, such as significant non-billable staff time, especially when medications are sent to an external pharmacy and the cancer center receives no compensation in return.5 Successful programs, such as the one by Mancini and colleagues, have profit margins that accommodate a full-time pharmacist, full-time technician, and a full-time pharmacy billing specialist, all dedicated to an oral chemotherapy management program at a community cancer center.6 Oncology pharmacists are the experts on cancer drugs and can play a pivotal role in establishing and managing such programs. Yet, they continue to face financial hurdles of billing due to lack of provider status and the complexity of assigning a dollar value to the interventions and services they provide. Limited studies track the outcomes of pharmacist-led interventions in promoting adherence to, and safety of, oral chemotherapy, especially when oral chemotherapy is decentralized from the cancer center to the community or specialty pharmacies.

Telehealth in Oncology—Teleoncology

One way to overcome the challenges and limited resources for oral chemotherapy is to implement teleoncology, which is the application of telemedicine to advance cancer care, including diagnostics, treatment, and supportive care.7 Disparities in cancer care delivery between intravenous and oral chemotherapy can be improved by establishing telecommunication infrastructure—for example, an oral chemotherapy telehealth clinic, run by clinical faculty contracted with a community cancer center, and staffed by pharmacy trainees.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Telemedicine Association underscore the use of telecommunication to promote health. While telemedicine has gained popularity during COVID-19, lessons learned from this experience may live long beyond the pandemic. Deploying patient-provider telehealth along the oncology care continuum was successfully implemented during the pandemic by a group of providers in California, who highlighted the critical need to further investigate the role of telehealth, not only during crises, but also to improve our routine care of patients with cancer in the future.8

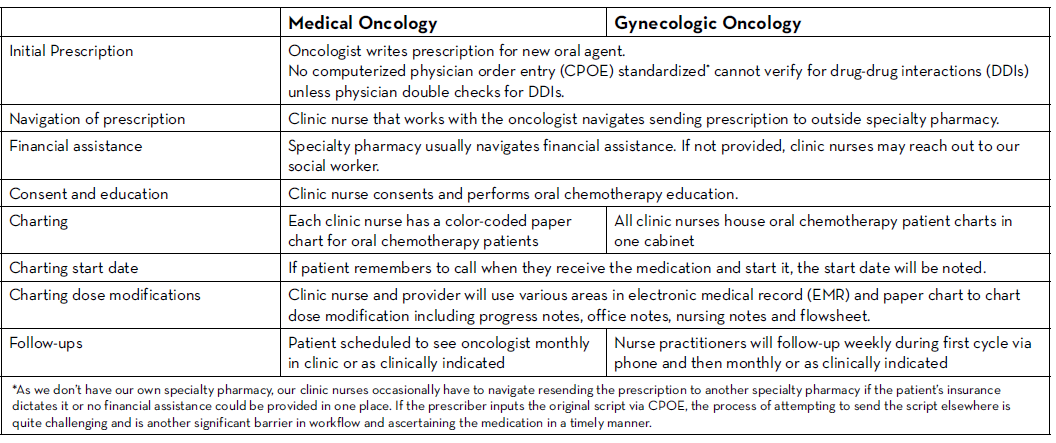

Older Oral Chemotherapy Patient Management at Our Cancer Center

The following outlines an oral chemotherapy telehealth clinic launched by clinical oncology pharmacy faculty and pharmacy student trainees from the University of Missouri Kansas City (UMKC) School of Pharmacy at Advent Health Cancer Center in Shawnee Mission, Kansas.

In an effort to standardize practice across the different clinics and switch from paper charts to a centralized online tracker, the oncology pharmacist had already proposed a new workflow related to the care of patients taking oral oncolytics. The cancer center management team and providers endorsed the proposal and agreed to pilot it; unfortunately, the pandemic delayed the start date. However, various clinical support staff began working remotely, so management suggested that they could partially implement the proposal and switch patients on oral chemotherapy from paper charts to an online tracker.

The oncology pharmacist developed a training video to help navigate the switch from paper charts to the online tracker utilizing the Microsoft Teams platform to include all patients stratified by provider. Data collected in the tracker included the following: patient name, medical record number (MRN), diagnosis, oral oncolytic prescribed, prescription date, dose, insurance provider, specialty pharmacy, patient assistance program, date prescription sent, date prescription received, dates of initial consultation and follow-up with a PharmD, oral chemotherapy initiation date, week 1 through 4 follow-up assessment (by nurse practitioner or PharmD), monthly assessment, telehealth follow-up visit, and notes.

Piloting the New Oral Chemotherapy Remote Patient Monitoring Clinic

Phase I → Switching all patients on oral oncolytics from paper charts to the online tracker

Phase II → Following up on all existing patients via a telehealth visit using the pharmacy consult described below

Phase III → Establishing a standardized workflow for all new patients starting oral oncolytics

The completion of phase I allowed us access to all patients on oral oncolytics in one location. This was followed by developing a pharmacy consult note (including assessment of adherence, adverse events, medication-reconciliation, and a quality-of-life questionnaire) that was approved by providers who wished to enroll patients in this service. We explored multiple telehealth/telemedicine synchronous technologies during the pandemic. These included using the patient portal virtual visits, considering HIPAA protected Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and other mobile applications. Technology challenges included cost, image/sound quality (depending on internet quality), lack of internet and video access for some patients, difficulty remembering scheduled virtual appointments for both patients and providers, patients struggling to use the technology, and the need for more provider training. Phone calls with video capability by patient request worked best for our patients, and hence, was adopted for this telehealth clinic.

Subsequent steps involved training fourth year pharmacy students who were on their advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) month-long oncology rotation, and establishing a timeline to cover all patients. The steps below describe the pharmacy students’ training model developed by our faculty.

Student Training—TAMER Model

1. Teach:

- Students learn about the consult note. Each element of the note is reviewed in detail during their first week of rotation.

- Students are assigned patients to work up on Friday.

- Students are instructed to prepare for Monday telehealth visits and set the intention for meaningful and efficient interactions over the phone.

- Students are encouraged to have the patient’s EMR open during the call, as well as multiple databases (drug resource, herbal database, adverse event grading tool) that may be needed.

- Students are provided phone scripts approved by cancer center to introduce the call/telehealth service and to leave messages if patients don't answer.

- Students are instructed to inform faculty immediately in the event a patient discloses any adverse event greater than grade 1.

- Management of grade 1 adverse events such as nausea, diarrhea, constipation, fatigue, and pain are discussed in details and may be addressed during the telehealth visit.

- Students are encouraged to explore cues (unreported adverse events as well as issues identified regarding physical, social, emotional, and functional wellbeing) from the quality of life questionnaire built into the visit.

- Students will complete the consult notes on Monday afternoon. Any interventions are discussed with the faculty and then relayed to the corresponding provider in person on the same day. Faculty will then review all the notes and send edits back to students.

- Edited/reviewed notes are then added to patient’s EMR by the students, co-signed by faculty and forwarded to corresponding provider.

2. Assess Preparedness: The subsequent Monday, the faculty will discuss all the patients that students worked up on Friday and address any questions the students may have prior to any phone calls.

3. Modeling: Faculty models one real patient consult in real time while students shadow.

4. Example: Students then contact their first patient while faculty is present. Faculty may assist during the call if needed, and after completion of the call, faculty will review what went well and what can be improved with the students.

5. Repeat and learn: Students get to participate in this telehealth clinic for three to four Mondays during their rotation.

Challenges

We knew that implementing this new initiative during a global pandemic would be uniquely challenging. Nevertheless, with the collaboration of all cancer team members, we piloted this program with a few providers starting in June 2020. We are currently in the process of retrospectively collecting all the consultation data. This data will be discussed at provider meetings in an effort to get feedback and standardize the management of all patients on oral chemotherapy. A new chemotherapy workflow was developed and scheduled to begin in January 2021. All patients who start oral chemotherapy will be instructed to contact the clinic when they receive their medication to set an initial education/drug-interaction check visit with the oncology pharmacist in person or via telehealth. All patients will have weekly follow-up calls with an oncology pharmacist for the first cycle of therapy; and with a nurse practitioner or clinic nurse for subsequent cycles. Cancer center management and pharmacy will analyze the metrics and explore ways to improve and standardize prescribing and dispensing of these agents.

Closing Remarks

Establishing new, standardized workflows for an oral chemotherapy clinic, in the middle of a pandemic, challenged everyone involved to better observe the needs of their local sites and identify opportunities to innovate with limited resources. Using the TAMER model, our initiative to improve and standardize the oral chemotherapy workflow can lead to improved patient care and outcomes, while also providing a no-cost critical training opportunity for pharmacy students.

Teleoncology is a valuable service that can be utilized by pharmacists to provide access to quality cancer care with minimal disruption to cancer patients. We will continue to identify and measure quality metrics from this new workflow in order to further develop and refine processes to better serve cancer patients.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges and thanks Kyla Bidne, PharmD BCPS BCOP and Shanna Keiser, RN, for their guidance and review of the article.

REFERENCES

- DeCardenas R, Helfrich J. Oral therapies and safety issues for oncology practices. Oncol Issues. 2010;(March/April): 40-42. DOI: 10.1080/10463356.2010.11883499

- Food and Drug Administration. Hematology/Oncology (Cancer) Approvals & Safety Notifications. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/ resources-information-approved-drugs/hematologyoncology-cancer-approvals-safety-notifications. Last accessed December 18, 2020.

- Weingart SN, Brown E, Bach PB, et al. NCCN Task Force Report: Oral chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6 Suppl 3:S1-S14.

- Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, Chuen Li S. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient’s perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(1):269-286. doi:10.2147/tcrm.s1458.

- Mancini R, Kaster M, Vu B, et al. Implementation of a pharmacist managed interdisciplinary oral chemotherapy program in a community cancer center. J Hematol Oncol Pharm. 2011;1(2): 23-30.

- Mancini R, Wilson D. A pharmacist-managed oral chemotherapy program: an economic and clinical opportunity. Oncol Issues. 2012;27(1):28-31.

- Wysocki WM, Komorowski AL, et al. The new dimension of oncology. Teleoncology ante portas. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;53: 95–100.

- Liu R, Sundaresan T, Reed ME, Trosman JR, Weldon CB, Kolevska T. Telehealth in Oncology During the COVID-19 Outbreak: Bringing the House Call Back Virtually. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(6):289-293. doi:10.1200/OP.20.00199

New Year, New Goals: Six Keys to Surviving and Thriving

Kimberly Haverstick, PharmD, BCSCP

Assistant Director of Pharmacy, Infusion Services Manager, Cancer Institute Pharmacy

Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Little Rock, AR

It may be a bit cliché, but there’s something about the new year that stirs up nostalgia for what has passed and anticipation for what lies ahead. As that time of year rolled around again, I scrolled through my social media posts from the past year. At the end of December 2019, I was reflecting on my oldest child’s upcoming 10th birthday, and appreciating all of the change that had happened in that decade. I then came across a photo of my accounting text book, with the caption, “New year, new goals!” I was excited to be starting on my MBA degree. After being out of school for over 13 years, and having four kids in the meantime, I knew that this would be a challenge, especially on top of a full-time job. But I was up for it—it was time to move forward with this monumental goal. Little did I know just how challenging 2020 would be!

Storms are Coming

As I continued scrolling through my 2020 social media feed, a photo of a beautiful sunrise caught my eye. I had captured the red and purple sky, a sure sign that storms were brewing, on my way into work one morning. My caption said, “Storms are coming, but storms can be beautiful, too!” The date was March 11, 2020. Later that day, the first presumptive case of COVID-19 was detected in my state.1 Yes, storms were coming, indeed! In an instant, life turned upside down.

In those early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, change seemed to be happening at a faster rate and on a larger scale than many of us had experienced in our lifetimes. “Unprecedented” seemed to be the most fitting word. Across the nation, schools and businesses closed while parents navigated remote learning and childcare challenges. Employees and employers struggled with the drastic impact on the workforce and the economy.

For those of us in the healthcare industry, there were added challenges; we learned to care for COVID-19 patients, strug¬gled with capacity and staffing challenges, and worried about protecting ourselves and others with a less-than-adequate supply of personal protective equipment (PPE). We navigated the medica¬tion supply chain and educated the general public.

Surviving the Storm

In the midst of daunting obstacles, it was amazing to witness the response of so many creative, hard-working, and resilient people. Every day, I was impressed by the ingenuity and teamwork of everyone at my institu¬tion—from frontline workers all the way up to the C-suite.

Change was happening quickly; often, new policies were developed, only to be changed as more information became available. Every aspect of our jobs seemed to be under scrutiny and subject to rapid and drastic change, including scheduling and staffing, HR policies, COVID-19 treatment guidelines, infection prevention strategies, visitor policies, and daily screening practic¬es, among many other things. But with each new change, we rose to the occasion, and found creative ways to solve one problem after another, even if we had to re-solve them in a new way the next day.

How to Move from Surviving to Thriving

Looking back at the response of our institution, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences—and specifically the pharmacy department—I can pick out a handful of factors that I believe were keys to not just surviving this period of unprecedented change, but thriving through it.

First, excellent leadership. This was crucial both at the institu¬tional level and from our Chief Pharmacy Officer (CPO). Frequent communication was also key. From the beginning, our CPO set up a regular cadence of meetings with department leaders. For a peri¬od of time, we met daily to discuss every aspect of the pandemic’s impact on patient care, pharmacy and hospital operations, and our personnel. This allowed us to collaborate across the department to creatively and quickly solve and anticipate problems. The impact of COVID-19 was not uniform in all areas—for example, in oncology areas, patient care was mostly business as usual. But making sure leaders and clinicians from all areas of the department were included in the daily meetings allowed for a unique opportunity for people to volunteer time and resources to meet needs in other areas.

Additional noteworthy keys for success were flexibility, resourcefulness, teamwork, and resiliency. As pharmacists, we are accustomed to dealing with constant drug shortages, tight staff¬ing, evolving treatment guidelines, changing policies, emerging technologies, and new institutional initiatives. While this pandem¬ic stretched these challenges to the limit (and beyond), we were able to pull from past experiences, and apply lessons learned to the challenges at hand.

Lessons Learned

On a personal level, living, working, and leading through this pan¬demic has provided ample opportunity for reflection and growth. Am I leading and caring for my team (and my family) with empa¬thy? Is information timely and delivered in a way that is mean¬ingful and reassuring? How can I creatively manage resources to ensure patient care continues safely and as seamlessly as possible? Am I taking care of myself, so that I will maintain resiliency? How can I continue working toward goals—organizational, profession¬al, and personal—during these trying times?

In times of crisis, these considerations are vitally important. The reality is, however, that they were just as critical pre-pandem¬ic, and will continue to be in the future. Realizing that, I spent time reflecting on how I could leverage these lessons learned into practical tips for navigating future challenges—both large and small. Here is my own personal list:

- Be empathetic. Everyone—patients and caregivers, teammates and employees, leaders and administrators—has struggles. Empathy and kindness are crucial to building trust. Be willing to give people the benefit of the doubt whenever possible.

- Communicate regularly and effectively. Ensure that communication happens in a way that is meaningful to the recipients. Take time to listen and let people know you care. At work, consider utilizing multiple forms of communication, such as daily huddles, staff meetings, emails, bulletin boards, electronic communication boards, and whenever possible, one-on-one conversations.

- Be flexible. Volunteer to help in other areas if possible— not only will others appreciate the help, but also it can be personally invigorating. Be willing to change processes to meet new challenges. Think outside the box to solve problems creatively. Be patient with yourself and others when things do not go as planned.

- Be resourceful. Make the best use of resources (personnel, PPE, medications, etc.). Be creative in filling gaps. If possible, consider leveraging volunteers or students on rotation to help meet needs during staffing shortages. Consider cross-training and/or reallocating staff to areas of highest need. Find creative ways to conserve supplies and protective equipment. Stay on top of potential drug shortages, and explore every channel for procuring critical medications.

- Prioritize resilience. Know when to take a break. Ask for help when you need it. Spend time with loved ones. Engage in hobbies. And make it a priority to rest and relax.

- Do not lose sight of goals. During times of crisis, we often default to survival mode, which is a natural response. However, it is important not to forget about the goals you have set. Whether it be learning a new skill, furthering your education, pursuing a hobby, improving your health, or finding a new job, it is important to keep them in mind. While your time and attention might be pulled elsewhere during a true crisis, it doesn’t mean that all of your goals need to be on hold indefinitely. Consider how you might be able to continue making progress, even as you face challenges.

Bright Spots

Though 2020 was not what any of us expected, it was an oppor¬tunity to highlight just how strong, caring and resilient we are as a profession. In spite of all of the challenges—juggling work and family concerns, starting a graduate degree program, facing many unknowns, losing loved ones—I find myself in a nostalgic frame of mind.

I am grateful for the bright spots of 2020, and I am hopeful and excited as I look toward the future, whatever it brings. I’ll take the lessons learned, and continue my own personal journey toward being the best that I can be. If there’s been any constant in my career as a pharmacist, it’s that change is inevitable. Learning to not only survive it, but also embrace it and thrive through it, is indispensable!

REFERENCE

- Governor Hutchinson Confirms State’s First Presumptive Positive COVID-19 Case. Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson. https://governor.arkansas.gov/news-media/press-releases/governor-hutchinson-confirms-states-first-presumptive-positive-covid-19-cas. Published 2020. Accessed December 21, 2020.

Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic—Impact in Oncology Pharmacy Practice

Sylvia Bartel, MPH, RPh

Vice President of Pharmacy

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Boston, MA

During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare institutions and pharmacies worldwide have experienced significant challenges that have forced them to alter their standard operational and clinical practices. The shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), which received widespread media attention early on, was merely the beginning. Across the globe, healthcare organizations have reported other consequences of the pandemic, including delayed access to cancer, anti-infective, and supportive care medications, as well as a decrease in clinical trial referrals.1 Some institutions have also paused certain preventive services and cancer treatments.2 For example, breast, colon, and cervical exams decreased by 60% between mid-March and mid-June of 2020.3 Similarly, 44% of breast cancer patients reported delayed treatments.3 And like many other businesses worldwide, healthcare institutions have laid off non-critical staff and reassigned others to areas in the organization with which they are less familiar.1,4

In response to these challenges, and to keep patients and staff safe, healthcare institutions implemented rigorous infection-control practices and altered standard procedures. In addition to wearing face masks and practicing physical distancing—minimal preventive measures endorsed by numerous governmental health agencies—healthcare providers and pharmacies have installed plastic barriers at public service counters and increased telehealth options to deliver patient care, education, and medication reconciliation services.1,4,5 Pharmacies have adopted alternative methods for dispensing and administering medications in response to supply shortages and to limit contact between healthcare staff and patients. For example, some oncologists have reduced the number of patients on myelosuppressive medications.1 They may prescribe smaller doses of medications that cause neutropenia, or delay administration of these medications to limit the number of patients who require follow-up care.4 Other oncologists have transitioned patients from intravenous to oral medications whenever possible.1,4 To further reduce patient and staff contact, pharmacies have created self-service dispensing locations, set up curbside pickup, and mailed medications to patients.4

The COVID-19 Response at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI), like many other leading cancer centers, has been impacted both clinically and operationally. For example, the organization established a hospital incident command center structure, which included the pharmacy, to disseminate rapid updates (once or twice daily) across all departments through weekly meetings, daily huddles, and email communication. The pharmacy created its own internal command structure to ensure rapid communication between all areas of the pharmacy—infusion services, clinical services, and clinical trials/research pharmacy, outpatient/specialty pharmacy—and the rest of the DFCI healthcare team. Other institution-wide changes that affected pharmacy operations included employee, visitor and vendor screening protocols, staff relocation, and remote work options. New PPE and medication conservation strategies required the pharmacy to closely monitor its stock and work collaboratively with DFCI’s supply chain team.

5 Ways COVID-19 Changed Pharmacy Operations

In addition to adapting to DFCI’s institution-wide changes, the pharmacy revised its own operating procedures to ensure the safest protocols for medication preparation and dispensing. For example, we reduced the duration and frequency of on-site patient visits and decreased medication turnaround times, which was a goal we achieved early on in the COVID-19 pandemic and have been able to maintain since. To accomplish this, we have:

- adjusted where and how staff work,

- increased the number of medications prepared in advance for infusion therapy appointments,

- maximized use of the automated dispensing cabinet (ADC),

- used prescription delivery services to minimize contact between patients and staff, and

- adjusted medication administration—route, frequency, and dosage—to decrease the amount of time patients spend on site and to minimize their need for follow-up care.

Adjusting Where and How Staff Work

Approximately 40% of pharmacy staff have worked remotely since March. While those in leadership roles such as directors and managers and a portion of order verification pharmacists are working under a hybrid model that includes both remote and on-site hours, staff in clinical practice, research, informatics, and billing and regulatory compliance work entirely remotely. Clinical pharmacy specialists that have been working remote include those in the anticoagulation management service, pain and palliative care, and oral chemotherapy teach areas.

While this has been successful overall, there are many challenges associated with remote work. Staff need the necessary technology—desktop/laptop, multiple screens, internet connectivity—to access to the institution’s clinical and operational systems. Communication methods (e.g. Microsoft Teams, Business Skype) with clinical teams and internal pharmacy department staff must remain secure and HIPAA compliance needs to be maintained. Additionally, it is important for remote workers to stay connected and engaged with on-site staff as well as to maintain a work-life balance.

There have been no noted changes in productivity or major issues identified. We have also reassessed and expanded staff roles. While everyone is expected to assist each other with tasks that fall outside of their usual responsibilities, some have taken on significantly more or different duties. For example, outpatient pharmacy technicians have provided coverage in the infusion pharmacy processing and material management areas.

Increasing the Number of Medications Prepared in Advance

Early on in the pandemic, pharmacy staff began to identify additional medications that could be prepared before patients arrived for infusion therapy appointments. Staff selected medications based on the drug’s stability, the likelihood it would be used (i.e., the patient would receive treatment as scheduled to minimize waste), and the likelihood that physicians would not need to adjust the prescribed dosage. For medications that are weight based, such as trastuzumab and 5-Fluorouracil, the doses were based on previous weight or body surface area as long as these remained within 10%. And now, we regularly prepare the following medications prior to patient appointments:

- 5-Fluorouracil continuous infusion pumps

- Herceptin Hylecta (trastuzumab and hyaluronidase-oysk)

- Herceptin (trastuzumab)

- Keytruda (pembrolizumab)

- Opdivo (nivolumab)

- Perjeta (pertuzumab)

Using a daily report, pharmacy staff identify infusion therapy patients and prepare medications for them in advance. For morning appointments, the medication is prepped by the end of the previous day; for afternoon appointments, prep is done in the morning of the same day. Pharmacy staff also manages delivery of the medications to the infusion unit. By increasing the number of medications prepared in advance, the pharmacy hopes to reduce the amount of time patients wait for their appointments once on site. Since adding the aforementioned medications to our advance preparation list in August of 2020, pharmacy staff are already seeing a more efficient clean room operation because compounding occurs throughout the day instead of at peak appointment times (i.e., between 10:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m.). Further, there has been minimal drug waste. The flat dose medications can be used for other patients, and for medications dosed by weight or body surface area, the 10% dose variation threshold has kept waste to a minimum.

In the coming months, we plan to review our metrics to determine preparation time for each medication, the number of physicians signing orders in advance, and patient wait times in the infusion therapy unit. We also continue to identify other medications that might be suitable for advance preparation and are working with physicians to determine whether exams and infusion therapy can occur on different days for certain types of treatments and patients.

Maximizing Use of the Automated Dispensing Cabinet

To minimize patient wait time and foot traffic in patient care areas and reduce compounding in the clean room, we have identified additional medications that can be added to our ADC. We have adjusted the periodic automatic replenishment (PAR) levels to reduce the frequency of restocking. Examples of medications we have added to the ADC include 4 mg doses of Zometa (zolendronic acid) and 120 mg doses of Xgeva (denosumab).

Using Prescription Delivery Services to Minimize Contact between Patients and Staff

In addition to delivering medications to our infusion therapy unit in advance of patient appointments, our outpatient and specialty pharmacy units are developing a process to dispense oral contrast medications to patients prior to their on-site radiology appointments. The units are also mailing prescriptions to patients both within Massachusetts and in other states.

Adjusting Medication Administration

Patients with cancer are at greater risk of experiencing acute COVID-19 symptoms and dying because cancer treatments often cause immunosuppression.1,2,3 Therefore, physicians are decreasing the frequency of treatments and prescribing fewer myelosuppressive regimens when possible. For example, Keytruda (pembrolizumab) is often administered in 200 mg doses every 3 weeks, but we have been able to administer 400 mg doses every 6 weeks based on recent approval of an extended dosing interval. Physicians are prescribing Opdivo (nivolumab) in 480 mg doses every 4 weeks as opposed to 240 mg doses every 2 weeks as well. Patients are receiving Kyprolis (carfilzomib) weekly as opposed to twice weekly, and we have been able to substitute darbepoetin alpha (Aranesp) for epoetin alfa, its therapeutic equivalent, to reduce the treatment frequency. The utilization of standardized dosing supports the ability to prepare medications in advance of a patient’s visit as well as avoid any potential medication dosage calculation errors. Exploration of other medications that are suitable for dose standardization along with dose banding is being further explored.

Physicians are also prescribing oral or subcutaneous administration routes to reduce the frequency and duration of on-site treatments. Oral medications such as etoposide have been utilized for patients receiving intravenous etoposide on multi-day regimens. In addition, Ninlaro (ixazomib) has been prescribed instead of intravenous Velcade (bortezomib). Examples of traditionally intravenous medications that are now available for subcutaneous delivery include Herceptin Hylecta (trastuzumab and hyaluronidase-oysk), Rituxan Hycela (rituximab and hyaluronidase human), Darzalex Faspro (daratumumab and hyaluronidase human-fihj) and Phesgo (pertuzumab, trastuzumab and hyaluronidase-zzxf). Physicians are also increasing prescriptions of Neulasta (pegfilgrastim) including the on-body injector, to avoid patients needing to return to clinic for an injection and to minimize the risk of febrile neutropenia. Though there has been a reduction in clinical trial referrals, we have been able to mail oral investigational medications to patients already on study therapy.

As DFCI moves into the next phases of its COVID-19 response, we plan to continue practicing some of the changes implemented in our pharmacy areas. We anticipate certain staff will maintain a remote work schedule and that telehealth will remain a convenient and appropriate option for certain patients or certain points in a patient’s treatment plan. Our advance medication preparation protocols have improved workflow in our clean room and, we believe metrics will show, have reduced patient wait times in the infusion treatment unit. Delivering clinical trial investigational and commercial medications to patients by postal mail has proved to be efficient for staff and convenient for patients. Finally, we have realized the indispensable value of data analytics for monitoring—in real-time—the effects of our new processes, creating performance targets, and identifying trends that will determine long-term operational changes.

The DFCI pharmacy staff have demonstrated remarkable resiliency and flexibility during the COVID-19 pandemic; I am humbled by their commitment to our patients. I look forward to working with them as we continue to adapt—and improve—our processes.

REFERENCES

- Alexander M, Jupp J, Chazan G, et al. Global oncology pharmacy response to COVID-19 pandermic: Medication access and safety. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020; 26(5):1225-1229. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32408842/

- Schrag D, Hershman D, Basch E. Oncology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020; 323(20):2005-2006. doi: 10.1177/1078155220927450.

- Ducharme J, Barone, E. How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed cancer care, in 4 charts. Time. August 28, 2020. http://www.time.com/5884236/ coronavirus-pandemic-cancer-care.

- Pourroy, B, Tournamille JF, Bardin, C, et al. Providing oncology pharmacy services during the coronavirus pandemic: French Society for Oncology Pharmacy (Société Francaise de Pharmacie Oncologique [SFPO]) Guidelines. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020; 16(11):e1282-e1290. doi; 10.1200/OP.20.00295.

- Koster ES, Philbert D, Bouvy ML. Impact of COVID-19 epidemic on the provision of pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies [published online ahead of print July 2, 2020]. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021; 17(1):2002–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.07.001.

Pharmacist Contributions to Quality Improvement in Oncology Care Presented at the ASCO Quality Care Symposium 2020

Ann Schwemm, PharmD, MPH, BCOP

Senior Pharmacist

Flatiron Health, Inc.

New York, NY

Shahrier Hossain, PharmD

PGY-2 Oncology Pharmacy Resident

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Boston, MA

Gena Hoefs

PharmD Candidate-Class of 2021

University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy

Minneapolis, MN

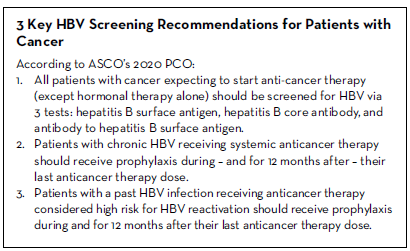

The virtual fall 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Quality Care Symposium showcased methods for measuring and improving the quality and safety of cancer care, including the work of many oncology pharmacists. Quality healthcare domains, as defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) include safe, effective, efficient, equitable, timely, and patient-centered care.1 Measurement of quality care should be practical, meaningful, inexpensive, and user-friendly. Four abstracts demonstrating pharmacy leaders measuring and improving quality care for patients with cancer are highlighted.

Organizational Partnership to Expand the ASCO Quality Training Program (QTP) to Oncology Pharmacists2

Pharmacists are critical in optimizing medication management and quality care in oncology patients. The HOPA Quality Oversight Committee (QOC) sought to improve educational opportunities in the area of oncology value and quality-based patient care for pharmacists. This led to discussion and a partnership with the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Quality Training Program (QTP) to develop a one-day workshop tailored to oncology pharmacists, aimed to strengthen their knowledge in quality improvement (QI) measures and strategies for practice improvement.

A pre- and post-workshop comparative assessment of attendees demonstrated the following on a 10-point scale: A 3-point improvement in knowledge and skills, and a 2.8-point increase in competence with 93% of attendees reported as very or extremely likely to use the new skills learned. The authors concluded that the workshop resulted in meaningful training in quality improvement measures for oncology pharmacists. Future partnership plans include additional one-day workshops and a modified ASCO QTP six-month course specifically for HOPA members.

State-wide Quality Improvement Addressing Overutilization of Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonists3

ASCO’s Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) Symptom and Toxicity Module (SMT) metric 28a focuses on the overuse of antiemetics, specifically of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists (NK1-RA) for low or moderate emetogenic regimens. A team including oncology pharmacists created a quality improvement project to support a reduction in use of NK1-RA when not indicated. Baseline measurements of performance, prescriber knowledge and beliefs, and pre-populated antiemetic order sets were assessed.

A quality improvement intervention was initiated and included practice and state-level performance reporting to the Michigan Oncology Quality Collaborative (MOQC); chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting education, and a value-based reimbursement related to measure performance. Initial responses assessing pre-populated antiemetic order sets showed that 23% had NK1-RA or olanzapine in moderate emetic regimens. Post-education, 48% of respondents had plans to, or had already, rectified their order sets. This ultimately improved performance from 27% to 19% (p<0.05) and below the 2020 QOPI mean performance measure of 31%.

Development and Implementation of an Evidence-based Malignant Hematology Clinical Pathway Program4

Clinical pathways often include a systemic approach to clinical decision support aimed at providing quality care while decreasing cost. Brahim and colleagues describe their institution’s implementation of a clinical pathways program to standardize practice and increase quality of care as measured by pathway adherence. A team of physicians, pharmacists, nurses, a quality manager, and information technology staff worked together to create pathway algorithms and review treatment plans for acute myeloid leukemia. This included treatments, laboratory testing, and supportive care (antiemetics, antimicrobials, and tumor lysis prophylaxis). The primary objective was to achieve a pathway adherence rate of 80% or higher.

A retrospective chart review one year after implementation was completed to assess adherence. Forty-four pre-pathway implementation patient charts utilizing best clinical evidence as a standard were compared to 44 post-implementation patient charts. There were 16 deviations pre-pathway. This included omitted medications, medications added, dose variations, different regimens, and supportive care. There were five deviations in the post-pathway group. Deviations included omitted medications, added medications, and different regimens. Pre- and post-pathway implementation adherence was 64% and 89%, respectively (p=0.006). The investigators plan to expand their program to other disease states, such as multiple myeloma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) while continuing to monitor adherence and program objectives.

Providing Uninterrupted Oral Oncolytic Therapies During the COVID-19 Pandemic5

The COVID-19 pandemic has created significant financial and logistic hardships for patients and pharmacies to provide continued oral oncolytic therapy. A team investigated whether the pandemic impaired access to oral chemotherapy at Tennessee Oncology’s medically-integrated specialty pharmacy. In a retrospective analysis, investigators compared medication possession ratios (MPRs) of the 5 most common medications prior to and during the pandemic (January–May), as well as copayments and use of financial assistance resources.

Consistent MPRs were demonstrated for the five most common therapies analyzed in 2019 versus 2020 (95.13% vs 94.86%). They also found similar aggregated copay amounts between the study periods and an increase in the use of copay cards (22%) and foundation assistance (12%) from 2019 to 2020. They concluded uninterrupted access to oral oncolytics and financial support services was provided throughout the beginning of the pandemic and attributed maintained MPRs to proactive and strategically-timed patient outreach.

Conclusion

Oncology pharmacists contribute significantly to improving quality and value metrics in the care of patients with cancer. Assessment of quality metrics and engagement in value-based contracts continues to grow and has become applicable to broader populations of patients with cancer in health-systems and oncology clinics. The impact of these on payment models continues to add pressure to meet these goals by the healthcare team including pharmacists. Regional and national publications and presentations aimed at quality improvement and research efforts will continue to show the value of the oncology pharmacist within patient-centered care.

REFERENCES

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

- Mackler ER, Morris A., Carro GW, et al. Organizational partnership to expand the ASCO Quality Training Program to oncology pharmacists. J Clin Oncol. 2020: 38 (suppl 29); abstr 198.

- Mackler ER, Procailo KM, Bedard L, et al. State-wide quality improvement addressing overutilization of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists. J Clin Oncol. 2020:38 (suppl 29); abstr 8.

- Brahim A, Vargas F, Wilkinson R, et al. Development and implementation of an evidence-based malignant hematology clinical pathway program. J Clin Oncol. 2020:38 (suppl 29); abstr 304.

- Arrowsmith E, Mitchell RL, Taylor JL, et al. Providing uninterrupted oral oncolytic therapies during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Oncol. 2020:38 (suppl 29); abstr 226.

The Straight Dope on CRISPR-Cas9 and Cancer

Diana Tamer, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Assistant Professor

University of Missouri Kansas City School of Pharmacy, Missouri

Hematology/Oncology Pharmacy Specialist

Advent Health Shawnee Mission Cancer CenterKansas City, KS

Introduction

Thirty years ago, the human genome project began, led by an international team of researchers looking to sequence and map all genes—together known as the genome.1 Completed in April 2003, it allowed us, for the first time, to read Nature’s complete genetic blueprint for building a human being: around 3 billion DNA base pairs using a four-letter DNA alphabet.1 Subsequent efforts included profiling patient cancers and exploring germline (inherited) versus somatic (acquired through life) genetic mutations.2 Cancer is a disease of the genome caused by a cell’s acquisition of somatic mutations in key cancer genes, sometimes in addition to inherited germline cancer driving mutations, so these efforts provided great insight into how cancers progress.

Initial cancer genome research focused on protein-coding genes, which together account for approximately 1% of the genome.1 To address this issue, the International Cancer Genome Consortium/ The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (ICGC/TCGA) and the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) Project performed whole genome sequencing and integrative analysis on over 2,600 primary cancers. They have now profiled more than 10,000 tumors and generated valuable data that illuminates the complexities of several cancer types.3-5 In 2020, researchers released six papers in Nature and 17 papers in other journals that could pave the way for full genome sequencing of all patient tumors.6 These sequences are being used in efforts to match each patient to a molecular treatment, the hallmark of precision medicine.

In the first part of the 21st century, twin revolutions in biotechnology and computer science offer enormous promise for technology to improve our lives. Together, biotech innovations in editing the genome of humans and other organisms, and computer science advancements in machine intelligence and machine learning, have the potential to confer tremendous benefits on humanity. The combination of these two tools could potentially accelerate progress in cancer research dramatically. Various applications could include modelling the genesis and progression of cancer in vitro and in vivo, screening for novel therapeutic targets, conducting functional genomics/epigenomics, and generating targeted cancer therapies.7

Dr. Jennifer Doudna, a professor of chemistry and molecular and cell biology at U.C. Berkeley pioneered the discovery of the fanciest molecular-scissors of the century, which has enabled us to edit DNA and ultimately genomes. Dr. Doudna rocked the research world in 2012 when she and her colleagues announced the discovery of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats associated nuclease 9 (CRISPR-Cas9); a technology that uses an RNA-guided protein found in bacteria to edit an organism’s DNA quickly and inexpensively.8 In 2020, Dr. Doudna and Dr. Emmanuelle Charpentier, chair of the Regulation in Infection Biology Department at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research and a Professor at the Hannover Medical School in Germany, won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for their work on this powerful gene editing system, increasing awareness of this technology.

What is CRISPR Gene Editing? 9,10

The process of CRISPR has actually existed for millions of years, having evolved to protect bacteria against viruses. The immune systems of certain bacteria use DNA sequences called CRISPR, which contain genetic material collected from viruses to which the bacteria have been exposed. When one of these viruses attacks the bacteria again, the matching CRISPR segment is copied to an RNA molecule that tracks down and binds to the virus’s own DNA, allowing a specialized cutting enzyme called Cas protein to chop off a piece of the viral DNA and kill the virus.

Once scientists learned how this worked in bacteria, they were able to extract CRISPR out of bacteria and reprogram the guide RNA to target any DNA sequence of the gene they wanted to alter. That sequence is then attached to a Cas enzyme (molecular “scissors”) to make cuts at the desired locations, adding or removing target DNA. In short, with this technology, we can rewrite the genome. And, this turned out to be simpler, cheaper, more efficient, more precise, and more flexible than previous gene-editing methods.

Somatic gene editing alters DNA of some of the body’s cells in humans to treat genetic conditions. Germline editing manipulates DNA in sperm, eggs, or embryos—affecting all or most-T-cells— and permitting the organism to then pass down those alterations to their offspring. In theory, rather than treating the disease, germline editing could eliminate the disease; and not just from the organism, but from its lineage completely.

A CRISPR Way to Screen for Cancer—A Sci-fi Dream or a Reality? 11-12

Aside from genome editing, CRISPR can also be used to help us rapidly and inexpensively read our DNA. This unexpected finding led to investigating the CRISPR-Cas protein system as a next-generation diagnostic. While Cas9 acts as a precise molecular scissors to produce one cut, Cas12 uses its guide RNA to search billions of letters to find the matching DNA target. Once it does, it starts cutting without stopping just like a paper shredder. Such a protein can be paired with a molecular fluorescent reporter that is ignited when the protein starts shredding and, as a reaction, generates a colorful explosion indicating that the target is present. The reaction detection can be freeze-dried and paper-spotted to generate a visual readout on a lateral-flow test strip, which is cheap and can be used at home, similar to a pregnancy test.

The new diagnostic tool developed by Chen and colleagues could help identify bacterial and viral infections (such as COVID-19), detect cancerous mutations in real time, and recognize new outbreaks before they spread. Cas12 has already been used in vivo to detect the presence of cancer-causing human papillomavirus (HPV) types, a common viral infection that can cause cancers – most commonly cervical cancer. CRISPR-based HPV diagnostics have had almost perfect accuracy. Cas12 can search through fluids such as saliva, blood, or even urine for a specific DNA match in minutes, at the point of care. This has many implications, such as detecting or screening for cancer early, or even diagnosing a viral infection during a pandemic in a prompt, non-invasive fashion.

Moving CRISPR-Cas9 from the Lab to Cancer Patients

The first-in-human testing of CRISPR was in 2016 by Lu and colleagues in China.13 They performed a Phase I clinical trial to assess the safety of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of PD-1 gene in autologous T-lymphocyte therapy in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The study enrolled 22 patients, 12 of whom were able to receive treatment. Two patients experienced stable disease, no grade 3-5 adverse events were reported, and off-target events were 0.05%. This has been followed by multiple ongoing CRISPR trials in China against esophageal, bladder, prostate, renal, and cervical cancers; as well as leukemia and lymphoma.14

The first-in-human CRISPR phase 1 clinical trial in the United States was launched in 2018 by Stadtmauer and colleagues.15 The study was designed to test the safety and feasibility of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing of T-cells, from patients with advanced refractory cancer. The trial enrolled two myeloma and one liposarcoma patients. They reported observing the edited T-cells expand and bind to tumor targets with no serious side effects related to the investigational approach. These patients were heavily pretreated, and since the trial, one patient has died and the other two have had disease progression. This study was not designed for efficacy, and the number of patients was small. Yet, it represented a historical step in the use of CRISPR-Cas9 in cancer therapeutics.

Improving Current Cancer Treatments with CRISPR

CRISPR may be used to improve efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.12 Applications under study include the generation of HIV-resistant T-cells with homogenous CAR expression, generation of allogeneic CAR-T-cells, and improving CAR-T cell function.12

Other active areas of study already in clinical trials include improving the efficacy of immunotherapy.23 Unleashing T-cells against tumors by blocking immune checkpoints such as cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) have been successfully used.23 Therefore, the knockdown of these genes using CRISPR, may be crucial to improve the efficacy of immunotherapies.23 A PD-L1 knockout in mice with ovarian cancer using CRISPR promoted anti-tumor immunity by increasing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and modulating cytokine/chemokine profiles within the tumor microenvironment, thus suppressing ovarian cancer progression.24

Future Avenues and Perceived Challenges

Future innovation may include the collaboration of two revolutionary technologies: CRISPR and artificial intelligence (AI). Machine learning based approaches to examine how changes in our DNA contribute to cancer already exist, and future CRISPR-Cas9 applied cancer therapeutics are likely to reach patients faster using AI to examine potential target and off-target DNA cutting outcomes and their implications.

CRISPR knockdown/knockout models may also offer a promising novel therapeutic approach for cancers that lack effective treatments, such as cervical cancer.25 HPV-associated carcinogenesis provides a classical example for CRISPR-based cancer therapies, since the viral oncogenes E6 and E7 are exclusively expressed in cancerous cells.25

Ethical concerns aside, when used for single-gene diseases or cancer, this technology may be the next breakthrough in genetic linked chronic diseases including cancer. Major safety concerns include but are not limited to the unknown long-term consequences of DNA manipulation and the irreversibility of this procedure. Practical and clinical challenges may include side effect management, especially if off-target effects take place; routes of administration; insurance coverage; and affordability. With every new cancer therapeutic modality that is innovated, there is both accompanying promise and peril. Hence, the opportunity for oncology pharmacists, with their crucial role of collaborating in healthcare teams, to make a difference addressing these concerns.

The effects of innovation are felt around the world. When it comes to medicine, the pace of that change is rapid, especially in oncology, and it’s only moving faster. Remarkable opportunities for good can also be misused. Both malicious intent and unintended consequences can create a real risk of harm for individuals, society, or both.

In 2018, He Jiankui, a Chinese geneticist, claimed to have used CRISPR-Cas9 on a set of twins and a third baby to make them HIV-resistant via editing of their CCR5 gene to create a resistance polymorphism in the children that had previously been seen in nature. His experiments were widely condemned as premature and irresponsible. A commission was formed and on September 3, 2020 the International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing released a 225-page report that offers a guide to the available testing and regulations, as well as the state of current research, and concluded that gene editing of human embryos is not yet reliable enough to use on humans in an ethical way.26 Written by dozens of scientists world-wide, the report stated that any country that permits its scientists to do so should limit the activity to severe, single-gene diseases such as sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, or Tay-Sachs.26

Closing Remarks

Gene editing and AI can radically change cancer therapeutics and is likely to have thousands upon thousands of applications. I believe that this potential for broad and rapid impact is at a scale that has rarely been witnessed in human history. The speed of these changes hastens an already urgent need for discussion on the plans for what to do when there are unmet therapeutic needs and when to proceed with caution especially when it comes to germline gene editing and unknown long-term consequences.

This is an exciting time to be practicing in oncology, witnessing novel therapeutics unfold, and providing new hope for our cancer patients. Yet, it is also a humbling experience that constantly reminds us that we are forever students, and our duty is to pass on this knowledge after we acquire it and consider not only its therapeutic implications, but also its ethical ones. As these technologies are pushed forward, so is our hope to see more scientists in government. There is a need to advocate for more diversity in our representatives to include scientists that can take the lead on these advances, and bridge the gap between science and policy via interdisciplinary collaborations.

Lastly, while using CRISPR in principle to cure sickle cell disease or some cancers may be a dream within reach during our lifetime, it’s not going to do much good if that technology is expensive and remains out-of-reach for the majority of patients. Therefore, the key to moving forward is to take this very exciting development and deploy it in a biomedically ethical, clinically responsible, and patient-affordable way.

Current Clinical Trials Actively Recruiting Using CRISPR in Hematology/Oncology in the United States

| Study Title | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Location | Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Study of Metastatic Gastrointestinal Cancers Treated with Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Which the Gene Encoding the Intracellular Immune Checkpoint CISH Is Inhibited Using CRISPR Genetic Engineering – IV infusion16 | NCT04426669 |

|

Intima Bioscience, Inc. |

| A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX130 (Anti-CD70 Allogeneic CRISPR-Cas9-Engi-neered T-cells) in Subjects with Relapsed or Re-fractory T or B Cell Malignancies – IV infusion17 | NCT04502446 |

|

CRISPR Therapeutics AG |

| A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX130 (Allogeneic CRISPR-Cas9-Engineered T-cells) in Subjects with Relapsed or Refractory Renal Cell Carcinoma – IV infusion18 | NCT04438083 |

|

CRISPR Therapeutics AG |

| A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX001 (Autologous CRISPR-Cas9 Modified CD34+ Hu-man Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells [hHSPCs]) in Subjects with Transfusion-Depen-dent β-Thalassemia – IV infusion19 | NCT03655678 |

|

Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated CRISPR Therapeutics |

| A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX120 (Anti-BCMA Allogeneic CRISPR-Cas9-Engi-neered T-cells) in Subjects with Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma – IV infusion20 | NCT04244656 |

|

CRISPR Therapeutics AG |

| A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX110 (Allogeneic CRISPR-Cas9-Engineered T-cells) in Subjects with Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Malignancies (CARBON) – IV infusion21 | NCT04035434 |

|

CRISPR Therapeutics AG |

| A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX001 (autologous CD34+ hHSPCs modified with CRISPR-Cas9 at the erythroid lineage-specific enhancer of the BCL11A gene) in Subjects with Severe Sickle Cell Disease – IV infusion22 | NCT03745287 |

|

Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated CRISPR Therapeutics |

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges and thank Gerald J. Wyckoff, Ph.D. for review of the article.

REFERENCES

- The Human Genome Project. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov/human-genome-project. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- Chow RD, Chen S. Cancer CRISPR Screens In Vivo. Trends Cancer. 2018;4(5):349-358. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2018.03.002

- International Cancer Genome Consortium. ICGC.ORG. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Program. https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/ organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546-1558. doi:10.1126/science.1235122

- Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature research. https://www. nature.com/collections/afdejfafdb/. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- Moses C, Garcia-Bloj B, Harvey AR, Blancafort P. Hallmarks of cancer: The CRISPR generation. Eur J Cancer. 2018 Apr;93:10-18. doi: 10.1016/j. ejca.2018.01.002. Epub 2018 Feb 9. PMID: 29433054.

- Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014;346:1258096.

- Mirza Z, Karim S. Advancements in CRISPR/Cas9 technology-Focusing on cancer therapeutics and beyond. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2019;96:13-21. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2019.05.026

- Panel Lays Out Guidelines for CRISPR-Edited Human Embryos. The Scientist Magazine®. https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/panel-lays-out-guidelines-for-crispr-edited-human-embryos-67913. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- Janice S. Chen et al., “CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity.” Science. Published online February 15, 2018. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6245

- Cook PJ, Ventura A. Cancer diagnosis and immunotherapy in the age of CRISPR. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2019;58(4):233-243. doi:10.1002/ gcc.22702

- Lu Y, Xue J, Deng T, et al. Safety and feasibility of CRISPR-edited T-cells in patients with refractory non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):732-740. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0840-5

- Clinical trial listings. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/ results?cond=crispr&term=&cntry=CN&state=&city=&dist=. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- Stadtmauer EA, Fraietta JA, Davis MM, et al. CRISPR-engineered T-cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science. 2020;367(6481):eaba7365. doi:10.1126/science.aba7365

- A Study of Metastatic Gastrointestinal Cancers Treated With Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Which the Gene Encoding the Intracellular Immune Checkpoint CISH Is Inhibited Using CRISPR Genetic Engineering. Clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ ct2/show/NCT04426669

- A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX130 in Subjects With Relapsed or Refractory T or B Cell Malignancies. Clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04502446

- A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX130 in Subjects With Relapsed or Refractory Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04438083

- A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX001 in Subjects With Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassemia. Clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03655678

- A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX120 in Subjects With Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04244656

- A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX110 in Subjects With Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Malignancies (CARBON). Clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04035434

- A Safety and Efficacy Study Evaluating CTX001 in Subjects With Severe Sickle Cell Disease. Clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03745287

- Chen M, Mao A, Xu M, Weng Q, Mao J, Ji J. CRISPR-Cas9 for cancer therapy: Opportunities and challenges. Cancer Lett. 2019;447:48-55. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2019.01.017

- CRISPR Therapeutics stock jumps on early gene editing data. Bizjournals. com. https://www.bizjournals.com/boston/news/2019/11/19/crispr-therapeutics-stock-jumps-on-early-gene.html. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- Zhen S, Li X. Oncogenic Human Papillomavirus: Application of CRISPR/ Cas9 Therapeutic Strategies for Cervical Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44(6):2455-2466. doi:10.1159/000486168

- Winter L. Panel lays out guidelines for CRISPR-edited human embryos. The-scientist.com. Published September 4, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2020. https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/panel-lays-out-guidelines-for-crispr-edited-human-embryos-67913

Virtual Interviews: Perspectives from Three Professionals

LeAnne Kennedy, PharmD, BCOP, CPP, FHOPA

Clinical Specialist, Blood and Marrow Transplant and Cellular Therapy

Resident Director, PGY2 Oncology Residency

Wake Forest Baptist Health

Winston-Salem, NC

Belinda Li, PharmD, BCOP

Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, Hematology/Oncology

Emory Healthcare

Atlanta, GA

Jessi Edwards, PharmD

Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, Oncology

Novant Health Cancer Institute

Charlotte, NC

Introduction

We asked one postgraduate year 2 (PGY2) oncology residency program director and two clinical pharmacy specialists to give our trainee readers tips on how to ensure a successful virtual interview. The result was different perspectives, from both the interviewer and interviewee points of view, based on their personal experiences. We hope you gain valuable insight from LeAnne Kennedy (interviewer), Belinda Li (interviewee), and Jessi Edwards (interviewee).

Before the Interview

What are the most common platforms utilized for a virtual interview?

LeAnne: Zoom and Webex are the most common platforms used by businesses, but there may be unfamiliar platforms too. You should be flexible and prepared for the unexpected and be gracious if things don’t go smoothly.

Belinda: The interviewer will typically send an invite in advance so you can familiarize yourself with whichever platform they’ll be utilizing for the interview. Practice using the platform before the date of interview if you’re unfamiliar with it.

Jessi: If you are familiar with the platform, it never hurts to perform a test run prior to the interview. Ensure you’ve installed the most up-to-date version of the platform on your device to avoid having to install/update the platform on the day of the interview.

Which type of audio or video connection is best (i.e., laptop vs. webcam and wearing headphones vs. computer audio)?

LeAnne: The most important thing is that you can hear and be heard. Make sure that all devices are charged and connected.

Belinda: If you have any distractions at home during the interview (e.g., children, pets, etc.), wearing headphones may help block out noise and keep your attention focused on the interview. Otherwise, just make sure you have a strong internet connection.

Jessi: It depends on your situation. I shared an office with other pharmacists during a recent virtual interview, so I scheduled my interview at a time I could be at home to avoid distractions and background noise. Additionally, I knew my internet connection at home was reliable so I would have a stronger internet connection.

What is the preferred background and/or location for a virtual interview?

LeAnne: The key is to be somewhere that you will not be distracted or interrupted. Find a plain background or at least something that is not distracting. I would not recommend moving from one location to another due to the chances of computers not connecting with each move.

Belinda: You need to be somewhere you won’t be distracted so you can stay engaged with your interviewers. If you have a private room where you can shut the door, that would be best. Plain and simple backgrounds are less distracting to your audience, and make sure the room has enough lighting.

Jessi: Do your best to find a private room and a blank background. I have even turned my home desk around so that the wall was behind me for a recent virtual interview.

What materials should the candidate have with them for a virtual interview?

LeAnne: Since it isn’t a live interview, you won’t need a paper copy of your CV. If you have made changes to your CV since submitting application, then I would be sure to email a copy (in PDF format) before your interview. The most important things to bring are a smile, positive attitude, and thoughtful questions about the program, institution, and also about the local area.

Belinda: Be prepared to share screen, especially if you’re presenting. Close out of everything else on the computer so you don’t accidentally share something else. Close out of your email and text notifications on your computer until the interview is complete.

Jessi: Turn off, or at least silence, your cell phone. Regardless of sharing a screen or not, your eyes may wonder if a text or email comes through, and this can make you appear disengaged or worse, you may miss a question or lose your train of thought. Just as with in-person interviews, having a notepad is good to take notes or to reference if you have prepared your own questions for the interviewers beforehand. Nobody is going to fault you for being proactive.

What information should the candidate prepare for a virtual interview and how might this differ from preparing for an on-site interview?

LeAnne: I recommend reading the interview letter/email several times to be sure you know what is planned for the day. If you have questions about the day, be sure to ask before the day starts. A few common questions:

- Will there be separate virtual sessions that you will need to log into?

- Is there a contact if there are technical difficulties?

- Will there be breaks built into the day for lunch and bathroom breaks?

- Is there a a video to watch before the interview (overviewing the site or city)? If so, watch it so that you can follow-up with insightful questions.

Belinda: You should be prepared for your interview similar to an on-site interview. Most of the questions you’ll be asked will be the same as on-site interviews. It’s important to still dress professionally and remain engaged even though you’re not on-site. Many institutions are still requiring presentations, so prepare for these as you would a normal interview.

Jessi: Just because you have a virtual interview does not mean you should prepare any differently. You should dress professionally and imagine as if you are in the same room as the interviewers. My recent virtual interview included more clinical questions, since a presentation was not required unlike other in-person interviews. I think there is an increased emphasis on preparing for those situations beforehand if no presentation is required.

Are there any other differences in preparation for a virtual vs. on-site interview that you would like to highlight?

LeAnne: It will be hard to convey your personality in a virtual interview, but it is important to be yourself as if you were there in the same room. Maintain professional posture and speech. Virtual interviews will help us all assess how adaptable we can be to different situations, so be flexible and gracious if things do not go smoothly.

Belinda: Virtual interviews may sometimes be one long continuous video conference with different people joining and exiting or have several sessions scheduled with different meeting invites. Make sure to keep track of which invitation you need to log into at the correct time and exit out of previous meetings when they are complete.

Jessi: Virtual interviews allow additional team members to attend when they may otherwise have been busy with patient care and unable to step away from their desk for an in-person interview. This means there are more people for you to ask questions of and get a better idea of the work environment and team dynamic. Take advantage of this opportunity by preparing broad questions that different pharmacists in different clinical areas can answer. On the other side of the coin, be aware that some of these pharmacists are multitasking on their end so while they may be attending virtually, they may not be providing their undivided attention. Try your best to keep your answers, and questions, interesting so that they remain engaged and will remember your interview down the line when it is time to review candidates.

During the Interview

How can the candidate learn more about the city or town during a virtual interview?