Chair Time Optimization

Kristin A. Hutchinson, PharmD

Oncology Clinical Pharmacist Trellis Rx

Atlanta, GA

Katelyn M. Brown PharmD Candidate 2021

University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy

Jackson, MS

Gregory T. Sneed, PharmD

Assistant Professor, Clinical Pharmacy and Translational Science

University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Pharmacy

Memphis, TN

Alexander R. Quesenberry, PharmD BCOP

Pharmacy Director Baptist Cancer Center

Memphis, TN

Introduction

Like many institutions nationwide, Baptist Cancer Center (BCC) has grown since its inception to include several infusion centers and remote clinics. One of the challenges of multiple sites spread throughout greater Memphis, is standardizing practices so that patients can have consistent, excellent care regardless of the treatment location.

One variation we discovered that could potentially translate into improved patient satisfaction, and eventually increased revenue, involved our premedication process. At many of our treatment centers, the medications meant to prevent reactions and adverse effects from chemotherapy were taking nearly as long to prepare, administer, and dwell as the chemotherapy administration itself. By streamlining as much of this process as possible, the improved efficiency would result in a lighter workload for the pharmacy department and nursing staff, and shorter infusion time for patients.

Three-Part Pilot Program

Over the course of several months, BCC’s busiest infusion center piloted process improvements using, in part, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) workgroup efficiency study as a model. The patients we targeted to measure these changes were those patients receiving carboplatin chemotherapy and 5 premedication agents.

The first modification we implemented to our premedication process began at the pharmacy level and involved moving from mixing IV piggyback mini-bags to providing nursing staff with IV push medications when possible. Shortly thereafter, medications that were available in oral formulations became preferred when appropriate for therapy.

Once oral and IV push formulations were adopted, the second major improvement was installing and integrating an automated dispensing machine for nursing staff to have immediate access to premedications upon order release and pharmacist verification.

The next and most recent improvement was to educate infusion nursing staff on how to maximize efficiency. Training included administering agents not requiring antiemetic treatment or hyper-sensitivity prophylaxis during premedication dwell time. Our pharmacists compiled a list of antineoplastic medications that would be appropriate to administer without premedication, and that were frequently used alongside our carboplatin-containing regimens. This list included medications such as bevacizumab, pembrolizumab, and trastuzumab, among others. When patients meeting inclusion criteria also received one of these agents, infusion nurses were encouraged to hang these agents during the 30-minute window that had previously been utilized only to allow antiemetics and antihistamines to be absorbed and effective.

So Far, Improved Efficiency and Less Chair Time

These changes have resulted in improved efficiency for staff and less time in infusion chairs for patients. In fact, recent data from our infusion center shows that our patients meeting inclusion criteria are spending an average of 42 minutes less per treatment in our infusion center chairs than they were at baseline, not quite a year and a half ago. Over time, we expect this multi-pronged approach to continually improve and extend far beyond this subset of patients. By manipulating variable factors where best practices do not yet exist, we can give patients back a bit of their day while still ensuring adequate antiemetic treatment and hypersensitivity prophylaxis. Optimizing patient flow through the infusion center over time will allow for more patients to be treated with minimal additional resources, improving revenue in the long term.

Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction has become a major focus nationwide following mandates of the Affordable Care Act and its Centers for Medicaid and Medicare (CMS) reimbursement implications.2 Research has shown that patient satisfaction can be tied to patient perception of quality of healthcare and ultimately in clinical outcomes.3 Patient satisfaction has always been a priority at BCC, but improvements can and should always be made. Not surprisingly, we have found from previous patient satisfaction surveys, that patients value their time. We have extended hours at one of our infusion centers to allow patients flexibility, and started using clinically appropriate faster infusion rates in certain chemotherapy regimens to minimize the time our patients spend in the clinic. There is evidence that implementing a series of changes over time improves outcomes more effectively than maintaining a single alteration.4,5

In keeping with that philosophy, the BCC infusion department implemented our step-wise quality improvement initiative to optimize chair time, which we hope will demonstrate our continued commitment to our patients while improving our own workflow.

For Patients, Quality Care Linked to Wait Times

Delivering efficient care is important for a number of reasons. Patient satisfaction correlates with reduced waiting time.2,3,6 Patients’ own perceptions of quality of healthcare, in fact, correlates with waiting time.3 Satisfaction is crucial to our continued development as a cancer center, and it ultimately can influence reimbursement rates and patient clinical outcomes. Adopting more efficient procedures will reduce chair time, potentially increasing patient turnover and revenue long term.

According to an NCCN study, data at one institution indicated that an infusion center chair is associated with $730 direct margin per hour.1 A study from MD Anderson Cancer Center in 2010, showed that implementing efficiency strategies “translated into more than $1 million in annualized potential financial opportunity for the cancer center.”1,4

Agents used for HEC (Highly Emetogenic Chemotherapy)/MEC (Moderately Emetogenic Chemotherapy)

Although hypersensitivity reaction prevention and antiemetic regimens are well studied, best practices do not yet exist for efficient premedication administration. The NCCN has recently begun surveying cancer care institutions nationwide in order to develop efficient and effective premedication processes, but currently the routes of administration, preparations of these medications, and dwell time of these medications once administered vary widely.1

Each of the 18 centers who responded to the NCCN survey reported a different premedication regimen for the same highly emetic chemotherapy treatment.1 Two centers that reported no wait time administered 3 oral medications concurrently—aprepitant, dexamethasone, and either ondansetron or granisetron.1 The center with the longest wait time of 60 minutes reported giving fosaprepitant IV individually followed by dexamethasone IV and palonosetron IV given concurrently.1

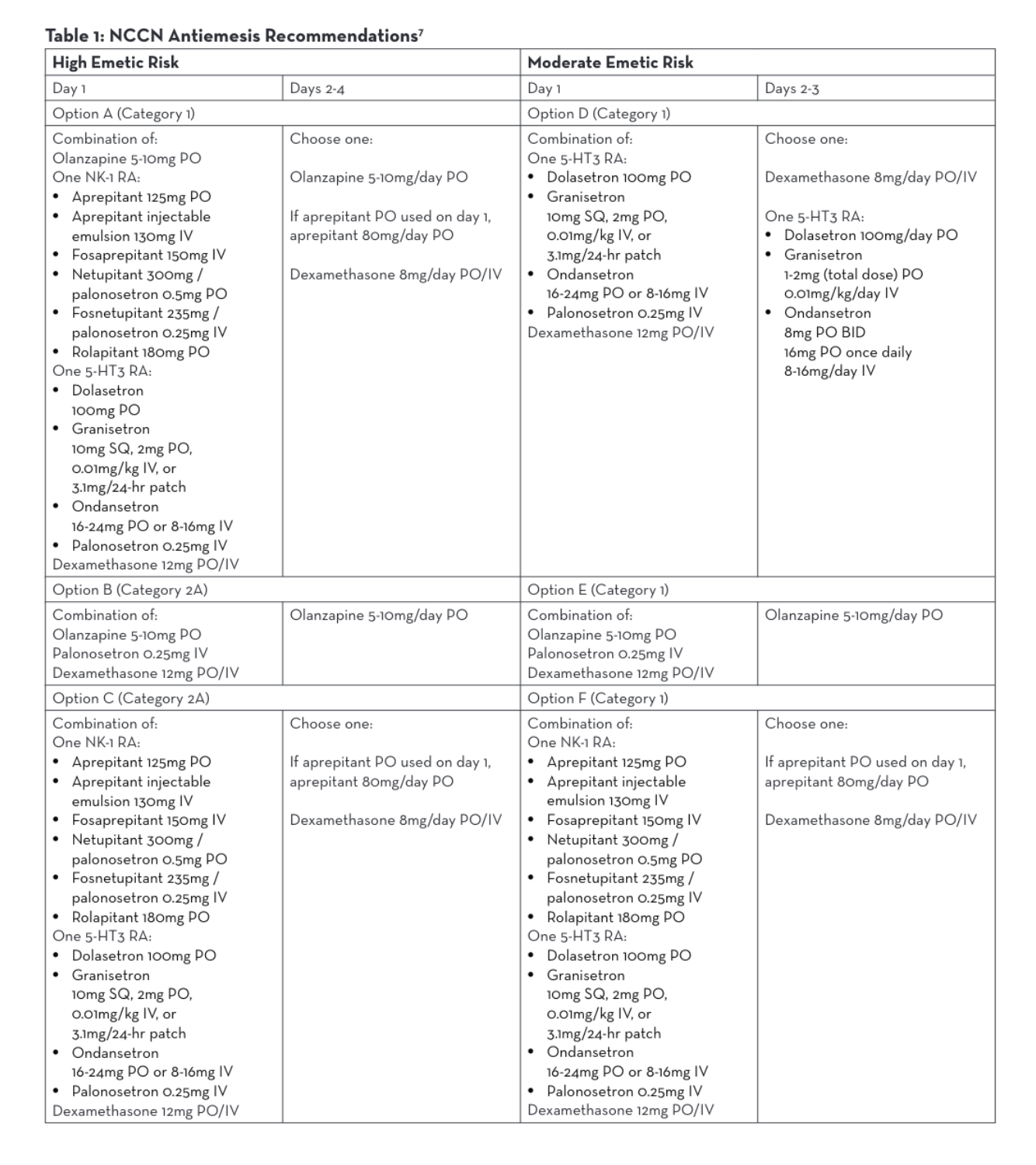

The NCCN Antiemesis Guidelines consistently allow for intravenous or oral formulations within 6 different combination options of antiemetic medications for parenteral chemotherapy, regardless of the emetic risk.7 Antiemesis regimens may consist of olanzapine, a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist (NK-1 RA), a serotonin receptor antagonist (5-HT3 RA), or dexamethasone. Both oral and intravenous NK-1 RAs and 5-HT3 RAs may be utilized per NCCN (Table 1).7 Many studies have been done to demonstrate similar efficacy between oral and intravenous antiemetic medications and neither NCCN nor Multinational Associate of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines address a preference.7,8,9,10,11 Therefore, BCC administers antiemetic regimens that are both efficacious and also lessen chair time.

One aim of Baptist Cancer Center’s Chair Time Optimization Project tested the adoption of oral and IV push premedication strategies. More specifically, when appropriate and available as an oral formulation, we use oral premedication. Examples include dexamethasone PO and ondansetron (Zofran®) PO. If medications are available in an IV-only formulation or a chemotherapy regimen specifies IV administration of premedication, we prefer a push over a piggyback barring anticipated adverse effects. By implementing these protocols, we have lessened chair time for select patients.

Antiemetic Agent Approval and Dosage Form Advancements

The manufacturers of antiemetic agents used within MEC and HEC have made advancements that assist in chair time optimization. A variety of changes to prescribing information based on clinical studies has allowed for more rapid administration of antiemetic agents compared to their original approval. In November 2017, aprepitant (Cinvanti) was originally approved as an intravenous infusion over a period of 30 minutes. In February 2019, the prescribing information was updated to include the approval of intravenous injections over a period of 2 minutes.12 The prescribing information for the majority of agents does include that the injection or infusion should be completed approximately 30 minutes prior to chemotherapy; however, studies have shown that the use of these agents within as quickly as 5 minutes before administration of chemotherapy demonstrated comparable antiemetic safety and efficacy.13 In addition, the available dosage forms of antiemetic agents have changed as well. The majority of agents are now available as an oral tablet, reconstituted solution, or even a prefilled syringe. The availability of these new dosage forms allows for stocking of the medications in automated dispensing cabinets for easier nursing access and expedited delivery to the patient.

New 797 Standards and Challenges in the Clean Room

Chemotherapy premedication route strategies must take into consideration new USP (US Pharmacopeia) 797/800 compounding standards. Many oncology outpatient IV room setups may be limited in meeting the environmental requirements to allow for the longest available beyond use dating. This limited beyond use dating (12 hours) can restrict the use of batch preparations and may cause additional demand for IV premedication mixing during peak rush hours. Forgoing the requirements of mixing IV premedications within an IV piggyback can allow pharmacy staff to focus their efforts on chemo-therapy preparations and improve compounding time.

It is important to note a few additional steps that will impact oncology pharmacy practices; including new Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) requirements of recording of lot numbers on compounded preparations and USP 800 implications that require all products, including premeds made in the biologic safety cabinet, or BSC, where hazardous products are compounded to require “PPE precaution handling required.”14

Costs and Impact on Reimbursement

When discussing changes in the route of administration one must consider the potential financial gain and loss. Compounding IV medications requires an infusion bag, IV tubing, syringes and needles. These supplies, as well as the labor of pharmacists and technicians, have a direct cost. By administering these agents by an IV push or via an oral route, infusion centers can avoid or reduce those direct costs. However, due to outpatient billing, potential exists for lower reimbursement in nursing administration fees. Nursing medication administration activities are generally reimbursable in the outpatient setting for IV infusions (96367) and for IV push (96375).16 2020 Medicare payment rates for those nursing administration codes are estimated at $31.40 and $16.60 respectively.16

It is also worth noting that Medicare part B does not individually pay for medications that fall under the packaging threshold ($130 as of 2020).17 Ideally, if the medication falls under the packaging threshold, the nursing IV push or infusion administration fees should cover the potential expense of the medication plus direct costs. Therefore, it might be most financially advantageous to utilize an inexpensive generic oral premedication.

Summary

At Baptist Cancer Center, variability in our premedication administration practices resulted in inefficiency for our staff and inconsistency for our patients. Since best practices do not yet exist, we found flexibility to establish our own. Dosage form advancements by manufacturers have provided faster yet equally efficacious administration. Utilizing oral formulations where available may minimize cost. By encouraging oral and intravenous push administration where appropriate for antiemetic treatment and hyper-sensitivity prophylaxis, infusion centers that might otherwise have been challenged by USP 797/800 constraints will have the ability to adequately premedicate patients for chemotherapy. We expect over time that patient satisfaction will continually improve, which is critical to reimbursement, and ultimately, patient outcomes. By implementing changes favoring efficiency and optimizing patient chair time, infusion centers and patients both can benefit.

REFERENCES

- Sugalski J, Kubal T, Mulkerin D, et al. National comprehensive cancer network infusion efficiency workgroup study: optimizing patient flow in infusion centers. J Oncol Pract. 2019; (15)5: e458-e466.

- Gourdji I, McVey L, Louiselle C. Patients’ satisfaction and importance ratings of quality in an outpatient oncology center. J Nurs Care Qual 2003; 18: 43-55.

- Sandoval GA, Brown AD, Sullivan T, Green E. Factors that influence cancer patients’ overall perceptions of the quality of care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006; 18: 266-274.

- Kallen, M. A., Terrell, J. A., Lewis-Patterson, P., & Hwang, J. P. Improving wait time for chemotherapy in an outpatient clinic at a comprehensive cancer center. J Oncol Pract; 2012; 8(1), e1–e7.

- Santibanez P, Chow VS, French J, et al. Reducing patient wait times and improving resource utilization at British Columbia Cancer Agency’s ambulatory care unit through simulation. Health Care Manag Sci 2009; 12: 392-407.

- Gesell SB, Gregory N. Identifying priority actions for improving patient satisfaction with outpatient cancer care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004: 19: 266-233.

- Ettinger D, Berger M, Barbour S, et al. National comprehensive cancer network clinical practice guidelines in oncology: antiemesis. NCCN. 2020;2:9-13.

- Aapro M, Gralla R, Herrstedt J, et al. Multinational association of supportive care in cancer / european society for medical oncology antiemetic guideline 2016 with updates in 2019. MASCC/ESMO. 2019.

- Gandara, D. R., Roila, F., Warr, D., Edelman, M. J., Perez, E. A., & Gralla, R. J. Consensus proposal for 5HT3 antagonists in the prevention of acute emesis related to highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Dose, schedule, and route of administration. Supportive Care in Cancer. 1998; 6(3), 237-243.

- Spector JI, Lester EP, Chevlen EM, et al. A comparison of oral ondansetron and intravenous granisetron for the prevention of nausea and emesis association with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Oncologist 1998; 3: 432-438.

- Jordan K, Sippel C, Schmoll HJ. Guidelines for antiemetic treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: past, present, and future recommendations. Oncologist 2007; 12: 1143-1150.

- Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm.

- Perez EA, Lembersky B, Kaywin P, Kalman L, Yocom K, Friedman C. Comparable safety and antiemetic efficacy of a brief (30-second bolus) intravenous granisetron infusion and a standard (15-minute) intravenous ondansetron infusion in breast cancer patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Cancer J Sci Am. 1998;4(1):52-8.

- The drug supply chain security act: improving the integrity of drug distribution. POWER-PAK CE. https://www.powerpak.com/course/content/113032.

- USP general chapter hazardous drugs-handling in healthcare settings. USP. https://www.usp.org/compounding/general-chapter-hazardous-drugs-handling-healthcare.

- Final 2020 Medicare coding & payment for drug administration services under the physician fee schedule. American Medical Association. 2019.

- Atkins E, Trunk S. 2020 proposal for Medicare Part B drug reimbursement: Business as usual. JD Supra. 2019.